TRI Fellow Profile: Coral Keegan

1) Where did you go for your fellowship?

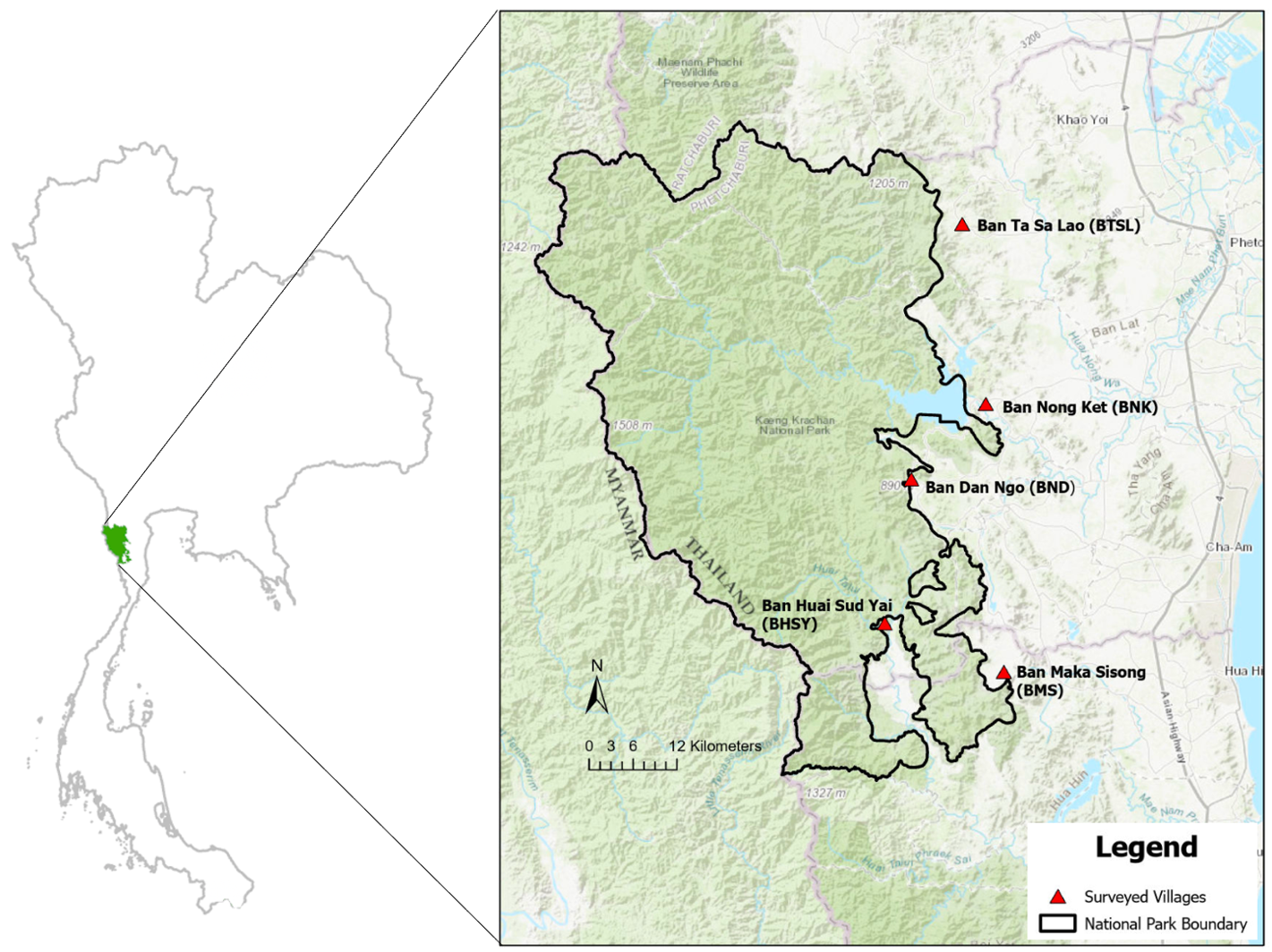

I was based in Kanchanaburi, Thailand at the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) field office. I conducted my research across five villages surrounding Kaeng Krachan National Park, Thailand’s largest national park located just a few hours southwest of Bangkok.

Image 1. Map of Kaeng Krachan National Park, located in south-central Thailand (left) and the five communities surrounding the park where research was conducted (right).

2) What research questions were you investigating?

I was researching how local ecological knowledge (LEK) can be used to inform conservation efforts for pangolins, specifically Sunda pangolins (Manis javanica), in Thailand. To understand this, I sought to answer questions such as:

1. Are pangolins present in the selected protected area? If so, what are local communities’ perceptions of these populations?

2. Are pangolins hunted in and around the protected area? If so, is this for subsistence or the illegal wildlife trade? Is it opportunistic or targeted?

3. Do local communities have any unique beliefs, attitudes, or opinions surrounding pangolins?

I developed this project after reading several peer-reviewed articles that used LEK to fill in information gaps and inform conservation strategies for pangolins in the Philippines, Cameroon, Republic of the Congo, and China.

LEK is particularly useful in studying pangolins because of their shy, nocturnal behavior. This combined with their low populations make them challenging to study using traditional ecological monitoring techniques such as camera trapping, radio tagging, etc. Local knowledge also has the added benefit of being less time intensive and more cost effective, and it can provide information about changes in a species’ population over time. Finally, LEK can provide insight into important cultural beliefs around species. For example, there are myriad beliefs and perceptions surrounding pangolins across their geographical range. In Nepal, many people believe they bring bad luck and kill them on sight. On the other hand, in several South African societies, pangolins are revered and whoever sees one is afforded special treatment by the local chief. Understanding these different beliefs is critical in developing successful conservation initiatives.

Image 2. This image of pangolin scales confiscated by Singapore customs agents put into perspective the severity of pangolin trafficking. (© 2019 Reuters)

3) Why did you choose to pursue this research and why in Thailand?

Before coming to Yale, I knew I wanted to focus my master’s research on pangolins. Pangolins are the world’s most trafficked non-human mammal and due to their elusive nature, little is known about them. For this reason, there is a great need for further research on all eight pangolin species found across Africa and Asia. During my first semester, I enrolled in Dr. Amity Doolittle’s Social Science Research Methods course so I could work through the development of a specific research project that would leverage my skills, create meaningful results for pangolin conservation, and be achievable within the timeframe of a two-year master’s program. After many conversations with people working in the field of pangolin conservation, I connected with Dr. Eileen Larney, the Chief Technical Advisor for the Zoological Society of London’s Thailand office. She was excited about my proposal to leverage local ecological knowledge to inform conservation efforts for pangolins, as the organization had begun to investigate this method in a nearby protected area but lacked the time and resources to continue with it.

Thailand was an ideal place to conduct this research because very little is known about pangolin populations within the country. To date, most research around pangolins in Thailand has been focused on trade routes, as pangolins are frequently trafficked from Indonesia and peninsular Malaysia and transported onwards to China and Vietnam, passing through Thailand’s northern border with Laos. Thailand’s pangolins have also been hard hit by the trade, making their shrinking populations even more challenging to study. Due to this lack of data, the Thai government has been unable to develop a country-level pangolin conservation management plan.

Lastly, I studied abroad and interned in Thailand during my undergraduate career, and so was already familiar with the language, culture, food, etc. which made it easier to dive in and hit the ground running.

Image 3. The mountainous semi-evergreen rainforest of Kaeng Krachan National Park supports a wealth of biodiversity.

4) What do you think is needed to understand or improve the situation around pangolins?

I think we just need more information in general, whether that be on local knowledge, pangolin ecology, trafficking routes, consumer perspectives, etc. All these elements help conservationists better understand what can be done to develop successful conservation strategies and decrease the overall demand for pangolins.

5) What challenges did you experience in your research?

Constantly changing plans. I was warned by fellow researchers that this would be the case, but as a “planner” this was hard to accept. But sure enough, as soon as we made a plan, something would change and upend our entire schedule. Challenges included finding available times to meet with community leaders, locating a place to stay near each village, finding times to speak with community members that were convenient for them, etc. One thing that was surprisingly not a challenge was people trusting us. I was worried that people would not want to discuss pangolins or pangolin hunting since it is widely known to be illegal. However, people were extremely generous with their time and knowledge.

Image 4. Coral and ZSL translator Saravanee Nampusak review village boundaries with the community leader of Ban Dan Ngo.

6) How do you want to use your research? How do you think your research will be used?

Using local knowledge to complement ecological research and inform conservation strategies is relatively new and still not widely accepted in the scientific community. I hope that this work can add to the growing research on local ecological knowledge (LEK), highlight its value in the field of wildlife conservation, and help to elevate its status in academia.

I have presented my preliminary findings at several conservation conferences, and hope to continue to share these results through publication in a peer-reviewed journal. I am currently in conversations with a PhD student from the Center for Wildlife Studies in India who analyzed similar LEK data for ZSL in Thailand’s Khlong Nakha landscape. We would like to co-publish a paper that will combine our findings from these different sites and hope that this will lay the groundwork for similar studies across Thailand’s protected area network.

Finally, I hope that this information will help guide ZSL’s educational and community engagement efforts with communities surrounding Kaeng Krachan National Park so they can become stewards for pangolin conservation in the region.