The evolution of Indonesian waste banks: Two tales, two cities, one reality

The evolution of Indonesian waste banks: Two tales, two cities, one reality

Sam Geldin, MESc1

Abstract

As local governments, NGOs, intergovernmental organizations, research institutes, foreign development agencies, and a host of community actors on-the-ground produce and consume best practices, it quickly becomes easy to lose track of the bigger picture outcomes. This case study uses a digitally documented best practice, the creation of Indonesian waste banks, as an example of how two institutions (specifically, a private sector foundation for corporate social responsibility and an intergovernmental initiative run by a think tank) duplicate and erase each other’s role in knowledge creation. Through nearly 40 semi-structured interviews and document analysis, this research explores the consequences of misattribution of institutional knowledge. Evidence suggests that systemic lack of coordination and difficulty of tracing institutional impacts can lead organizations to duplicate efforts and reinforce inefficient flows of knowledge and resources. This study’s results, in effect, will help direct practitioner efforts to restructure institutional incentives to cooperate, attribute knowledge, and thus disseminate climate adaptation strategies with greater targeted impact to groups that need them the most.

Introduction

While Indonesia has long sought to improve local infrastructure access, its guiding policies in sectors like waste management have changed only recently. New and innovative approaches to develop sustainably were motivated in part by demographic trends between 1990 and 2000, as Indonesia’s urban population increased by more than 30 million (UN-Habitat and UN-ESCAP, 2015). In effect, waste disposal sites and other public services simply could not keep up with the increased demand. However, political reforms in the early 2000s, which gave Indonesian municipalities more administrative power, exacerbated challenges to collect and integrate waste regionally. As serious public health concerns became manifest, local governments began recognizing the growing need for improved and diversified solid waste management practices (Damanhuri et al, 2014).

Two events in particular prompted a strategic shift in Indonesia’s waste management efforts. In 2001, the overwhelming stench of Surabaya’s single brimming landfill prompted public protests and a citywide waste management crisis after its closure (Ramdhani et al, 2010). Similarly, in Indonesia’s third-largest city of Bandung, heavy rains and poor operating practices in 2005 triggered the collapse of a major dumpsite onto adjacent villages of pemulung (waste-pickers), resulting in nearly 150 deaths and one of the deadliest waste slides ever recorded (Lavigne et al, 2014). Public discontent in the aftermath of this disaster galvanized a sense of urgency to replace open dumps with legally mandated sanitary landfills (Damanhuri et al, 2014). However, limited city budgets and technical capacity, as well as a lack of identified alternatives to stem the expansion of temporary dumping sites, prevented widespread action. In the wave of reactionary provisions that followed Bandung’s tragic events and subsequent waste relocation emergency, the national government passed the Solid Waste Management Act of 2008, which prioritized reducing rather than merely collecting waste (Damanhuri et al, 2014). While the law laid the foundation for more comprehensive waste management at the local level, community-based recycling initiatives continue to play a considerable role in meeting waste reduction targets (Meidiana & Gamse, 2010).

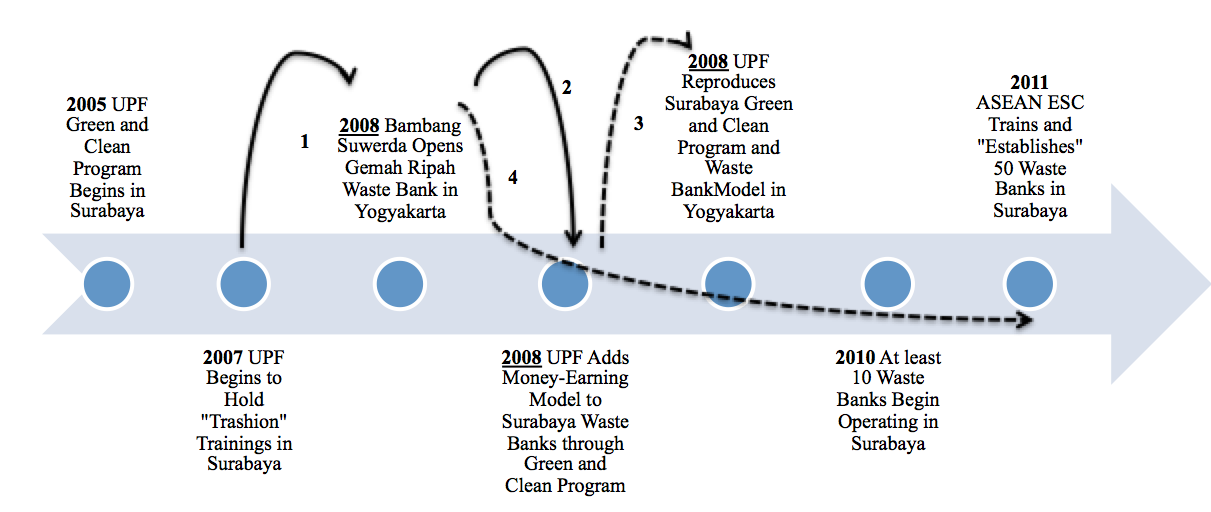

One particular practice, collecting recyclables through community waste banks, illustrates not only the power of local governments in customizing sustainable solutions, but also the power of external actors in shaping city-to-city knowledge exchange. Below, I detail the series of events that led to widespread local adoption of waste banks in Indonesian cities, as well as the, at times, conflicting narratives of two major internationally-rooted organizations that disseminated the strategy, the Unilever Peduli Foundation (hereafter UPF) and the Environmentally Sustainable Cities Model Program (supported by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and hereafter, ASEAN ESC).

My account was produced using a number of sources: academic literature, news articles, interviews with representatives of the two major institutions and other stakeholders, a field visit to a recently established waste bank in Sumatra, and a host of institutional reports and other publicly available web content. While further investigation would provide a more detailed timeline of waste bank dissemination, this summary aims to capture the most critical elements. Ultimately, the two organizations’ interconnected but different stories illustrate the ease of erasing an institution’s attribution to a best practice,2 as well as the deeply engrained, often invisible role of institutional competition. The discussion highlights how misattributing knowledge can enable and conceal duplication of efforts, and in effect help explain why resources often never reach the beneficiaries that need them the most.

Surabaya’s Green and Clean program

The first major champion of interest, UPF, acts as Indonesia’s corporate social responsibility branch for the eponymous British-Dutch consumer products company. Formed in 2000, the foundation initially intended to improve the water quality of Surabaya’s Brantas River near one of UPF’s factories.3 However, UPF traced the river’s pollution and tendency to flood directly to local residents, who dumped untreated solid waste directly into the water. As a result, the organization quickly acted upon the need for more comprehensive waste management as the means to enhance watershed management.

Through a multifaceted but targeted approach, the foundation’s efforts soon began to reap results. UPF trained 45 local housewives in the Surabaya subdistrict of Jambangan in 2004 as volunteer motivators (known as Environmental Cadres or Agents of Change) to host community meetings and educate roughly a dozen interested households each about recycling and composting practices (Fig. 1) (Ramdhani et al, 2010). In just two years, 90% of households had participated, diverting three-quarters of the community’s total waste from the landfill. This prompted UPF to partner with the Jawapos newspaper and the city government to reproduce the model as part of what they called the Green and Clean Program (Tahir et al, 2011). Together, they launched biennial competitions in over 100 subdistricts of Surabaya, between 2005 and 2008, to see who could divert the largest volume of trash (Ramdhani et al, 2010). Incentivized by neighborly competition and public prestige, higher performing subdistricts helped institute recycling efforts in lower performing subdistricts and in effect, waste flows in nearly all of the communities began to slow.

The scale and complexity of the Green and Clean Program expanded in concert with its success. It spread to communities in Jakarta in 2006, to Yogyakarta in 2008, and to ten other cities, soon incorporating more than 100,000 Environmental Cadres working in millions of households (Ramdhani et al 2010; Tahir et al, 2011). Civil servants, university students, and teachers began to join cadres of housewives, partly a reflection of the cultural emphasis on neighborly relations, civic service, and patriotic gotong royong (or mutual cooperation) (King and Idawati, 2010). In addition, the program began to include other components and local variations. One notable project in 2007 included teaching housewives in Surabaya how to make marketable trashion handicrafts, such as handbags and hats, from a portion of the plastic waste collected. The waste for handicrafts would be collected in a ‘bank’ for storage until ready for assembly and sale, supplementing streams of household and waste bank revenue by as much as 400,000Rp each (Ramdhani et al, 2010; Winarti, 2008). Surabaya’s model for waste reduction, income generation, and community empowerment has since won a host of international awards and influenced local initiatives in places like Japan, Nepal, Thailand, and the Philippines (Ramdhani et al, 2010).

Yogyakarta’s first waste bank

While UPF’s Green and Clean Program likely planted the seed that gave rise to Indonesia’s first recognized waste bank, the extent to which UPF influenced the dissemination of waste banks throughout Indonesian cities remains debatable. The whole story begins in the city of Yogyakarta during the time period when Surabaya’s Green and Clean Program spread. According to an interview by the national newspaper Kompas, a public health lecturer named Bambang Suwerda saw television coverage of communities using a ‘waste bank’ to store trash and then recycle it into more useful products (Prihtiyani, 2010). The model inspired him to conceive of a waste collecting facility that actually functioned like a conventional bank, where community members could directly exchange recyclables for cash. Motivated by his life’s work of promoting environmental health in his community, he founded what is now considered Indonesia’s original waste bank, Bank Sampah Gemah Ripah, in the district of Bantul in 2008 (see Fig. 1) (Prihtiyani, 2010).

To reap the bank’s benefits, customers would separate household paper, plastic, and glass into large bags, and bank tellers would itemize and record the total guaranteed price by weight (see Fig. 2) for sale to recycling facilities. After several months of waste savings, customers could access their earnings with a valid receipt (see Fig. 2) and sometimes secure more than half of their monthly living expenses, all while reducing community litter and informal waste picking. Since its inception, the bank diverted more than 1,000 lbs. of inorganic waste each month, retained 15% of collected revenue to cover operating costs, and gained extra revenue by selling finished waste handicrafts (see Fig. 2) (Maeda et al, 2011). Suwerda soon won nationwide notoriety for the success of Gemah Ripah, and the model’s flexibility gave it a life of its own outside Yogyakarta.

Around the time of Gemah Ripah’s founding, a vast array of actors became involved in waste bank dissemination and many novel innovations soon emerged. Impressed by the model’s economic sustainability and incentivized by corporate social responsibility, the Indonesian private sector began partnering with other interested NGOs and communities to invest in more banks (Lubis, 2015). Waste banks promptly spread to dozens of other subdistricts in Yogyakarta—often through study tours—and new banks began to emerge both organically and independently in other cities through networks of businesses, nonprofits, and civil society representatives (Phelps et al, 2014).4 Communities tailored their waste bank procedures to local needs and desires. For instance: some bank staff got paid and others volunteered; some banks became a learning tool for schoolchildren and others became distribution outlets for handicraft saleswomen;5 some banks collected business and retail waste in addition to residential waste; and some banks operated strictly as community-based organizations and cooperatives, while others were managed as public-private partnerships (Wijayanti and Suryani, 2014). Individual banks also developed unique service options so that customers could exchange their waste savings for over-the-counter transactions. Banks began offering kiosks and mobile apps for customers to use their waste saving credits to pay for food and household supplies,6 utility bills, health insurance,7 schooling fees, and property taxes (IGES, 2015; Idrus, 2014; Hajramurni, 2015).

Of course, a waste bank by itself does not necessarily constitute a best practice. Successful outcomes depend on the local context and will not follow if, for example, communities do not express a need or active enthusiasm to participate, if customers lack proper recycling education, if bank staff lack sufficient managerial training, or if price manipulation or oversupply of waste cause the redeemable value of recyclables to dip below profitable levels (Jeffery, 2013).8 Likewise, informal waste ‘mafia’ collectors must not feel threatened, as they could cut off service to new banks (Jeffery, 2013). However, the majority of waste banks have overcome such challenges and many ultimately benefited from the financial resources and advisory support of existing community-based waste networks.

As one of the key networks already educating communities about recycling practices, UPF certainly became one of the primary means for waste banks to proliferate. In the same year that Suwerda founded Gemah Ripah in Yogyakarta, UPF’s Green and Clean Program in the city of Surabaya incorporated waste banks into its competition criteria.9 When new cities joined the Green and Clean Program, they also inherited the program’s institutional resources to mobilize hundreds of waste banks. By 2015, UPF’s program alone claimed considerable impact in 17 cities and 12 provinces, supporting 1,258 waste banks, recruiting 55,558 customers, recycling over three tons of inorganic waste, and exchanging more than 3 billion Rp (Unilever, 2016). Yet as shown below, claims of disseminating knowledge of and skills to manage waste banks quickly become difficult to distinguish.

A second, conflicting waste bank narrative

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ Environmentally Sustainable Cities (ASEAN ESC) Model Program—the second notable institution of interest, an intergovernmental association—complements but also challenges UPF’s role disseminating waste bank knowledge. ASEAN member states founded the ASEAN ESC Model Program in order to promote collaboration among the region’s environmentally sustainable cities. Administered by the Japanese-based Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES) and funded in part by the Japanese government, ASEAN ESC (like UPF) works to scale up local-level pilot projects and facilitate city-to-city exchanges.

ASEAN ESC’s story begins in 2011, three years after waste banks became part of UPF’s Green and Clean Program. Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment, which wanted to replicate Yogyakarta’s waste bank model throughout 250 cities across the nation, partnered with ASEAN ESC to start holding waste bank training workshops in Surabaya (IGES, 2012). Initially, ASEAN ESC and the Surabaya local government claimed that there were only six existing waste banks in the city, all of which operated under a model different than Yogyakarta’s (ASEAN ESC, 2011). Yet this assertion directly conflicts with statements made by UPF and independent researchers (Wijayanti and Suryani, 2014).10 Back in 2008, UPF helped already existing Surabaya waste banks integrate Bambang Suwerda’s money-saving concept into their operations.11 Likewise in 2010, Wijayanti and Suryani (2014) reported fifteen, not six, waste banks in Surabaya. Rather than assume ASEAN ESC and UPF’s different accounts intended to mislead observers, such inconsistencies may underscore broader concerns of institutional coordination and evaluation of impact.

Understandably, most government and non-government organizations struggle to completely trace the spread of best practices because they lack enough time and documentation. Considering the myriad of interactions between government officials, private sector donors, NGO implementers, and individual community members, there are many obstacles to accurately detail all the exchanges of knowledge related to just one waste bank. Plus, an institution could also undermine its own legitimacy by choosing to document the role of other actors in the first place. Presumably, institutions like ASEAN ESC have no interest in mentioning the perhaps greater knowledge disseminating power of hidden informal middlemen (pengepul or pelapak) who transfer large volumes of waste from waste-pickers and waste banks to recycling facilities (Tuori, 2012). Such loosely organized informal actors show that they could do much of the information dissemination that ASEAN ESC and other institutions claim to do, for less money and technical support. Yet organizations (both ASEAN ESC and UPF) that do not attempt to trace the cascading influence and context of their actions, let alone acknowledge limits to their own impact, perpetuate the uneven exchange of information resources.

When knowledge leaves no trace

As evidenced by the temporal discrepancies of ASEAN ESC’s and UPF’s claims, the manner in which both ASEAN ESC and UPF promoted their goals and achievements illustrates two fundamentally different, institutionally-centered accounts of how Indonesian waste banks developed and spread. On the one hand, UPF’s main online summary of its environmental achievements, which included launching the Green and Clean Program and dozens of waste banks in Surabaya, erases the city of Yogyakarta’s innovative role in developing the model in the first place:

“Under the name of ‘Green and Clean’, we collaborate … closely together with government, NGOs and community [sic]…The success of this [community waste bank] programme can be seen from the total unit of waste bank [sic], number of people involved and also the total of waste [sic] that is collected and sold…[T]his concept has been learning and developing [sic] since 2008. We are sharpening the model …(Unilever, 2016).” Emphasis added.

While UPF certainly should not be expected to dwell on the origins of the model it promotes, the fact that the organization engaged with many different actors and assumed credit for founding over 1,000 waste banks leaves the impression that UPF’s waste banks did not duplicate existing efforts. Yet UPF’s 2008 Green and Clean Program replication in Yogyakarta arguably did not need to found additional waste banks in the same area where Suwerda’s waste bank model began and had already spread, acquired resources, and assumed different variations. Knowing the context of Yogyakarta, as the epicenter of Suwerda’s waste bank innovation and the likely source of UPF’s waste bank model, reframes the otherwise laudable outcomes of Unilever’s activities in Yogyakarta (Rosdiana, 2013). Would UPF’s same actions in another medium-sized city, far removed from Yogyakarta’s established networks, have disseminated more knowledge and generated a greater long-term impact? We do not know.

ASEAN ESC, on the other hand, illustrates how even explicitly giving credit to another institution for its work does not mean its own influence is clear or equal. In the Model Cities initiative’s first annual report, ASEAN ESC actually acknowledges UPF’s work in Surabaya and asserts that “Although the waste bank concept was already known among the local community, this programme [ASEAN ESC] provided the catalyst to formally train communities and establish pilot waste banks on a wider scale” (IGES, 2012: 8). Unlike UPF, ASEAN ESC clarified the observed role of another institution. However because of ASEAN ESC’s lack of incentive to actively record UPF’s boundaries of influence, it effectively erased other critical pieces of information. For instance, the timing and language of a Kompas interview (Prihtiyani, 2010) presents reasonably strong evidence that UPF’s Green and Clean trashion trainings—widely publicized through its partnership with Jawapos—influenced Bambang Suwerda’s idea to establish the first recognized waste bank. This discovery that UPF’s activities likely inspired Suwerda’s waste bank remains unmentioned in ASEAN ESC’s story of waste bank expansion, as it requires effort to uncover and would diminish ASEAN ESC’s claim as a catalyst.

That is not to say ASEAN ESC had no influence in supporting the expansion of waste banks. The waste bank management trainings that it conducted for community stakeholders epitomize the crucial transfer of skills, rather than mere transfer of information, necessary to make a long-term impact. However ASEAN ESC’s partner, the Ministry of Environment, arguably played a comparatively greater role in waste bank dissemination. The ministry had already identified Bambang Suwerda as the brainchild behind the waste bank concept by 2011, inviting him to train stakeholders in other cities and assist in formulating a 2012 decree that outlined guidelines for waste banks’ official recognition (Maeda et al, 2011; Lubis, 2015).12 ASEAN ESC, meanwhile, almost exclusively disseminated knowledge to environmentally ambitious local governments, who were shortlisted for the ministry’s prestigious National Adipura Environmental Award.13 Surabaya, which received the award in addition to ASEAN ESC’s capacity building resources in 2011, already had waste banks operating for years through UPF’s Green and Clean Program. While there is certainly some merit to expanding capacity within a model city, denying access to capacity building resources in many smaller cities like Sibolga, which also received recognition for environmental leadership (Harfam, 2012), perpetuates knowledge gaps and reduces the efficiency of knowledge dissemination. By claiming credit for the spread of waste banks in 2011 from Yogyakarta to Surabaya, ASEAN ESC effectively erased UPF’s relevant actions and directed knowledge and resources to a city where those assets already existed (see Fig. 3). ASEAN ESC thus demonstrates how selectively represented institutional narratives can delay or prevent distribution of services to the cities in greatest need.

What can we take away?

While tracing the spread of a practice remains difficult, organizations should still take on the challenge. UPF and ASEAN ESC can both claim they influenced waste bank creation and knowledge dissemination because the evolution of waste banks as a best practice involved multiple back-and-forth innovations. Some Indonesian cities learned about waste banks from study tours to communities with ASEAN ESC-supported waste banks (like Balikpapan), some communities established waste banks as part of UPF’s program (like Makassar), some waste banks likely grew out of inspiration from both ASEAN ESC and UPF (Surabaya, Yogyakarta), and still others likely created waste banks independently through networks of informal waste collectors and private companies (Jakarta) (IGES, 2015; Ramdhani et al, 2010).14 However, written achievements of the two organizations should not conceal crucial context about each other’s influence. Institutions must have incentives to coordinate and must be held accountable for making vague or overstated claims of impact without actually attempting to trace a cause-and-effect relationship. Only through widespread adoption of more rigorous, transparent, evidence-based impact evaluations can “needs-led” development truly advance.

Note

The actions of specific organizations I reference in this article should in no way detract one from the overall quality or impact of such institutions’ work. My observations, intended to provide insight to the difficulty of tracing impact, merely provide a representative snapshot of the systemic challenges that all institutions face as they share knowledge.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Yale Tropical Resources Institute, the Yale Center for Southeast Asia Studies, and the Yale Center for East Asia Studies for supporting this research. The entire ACCCRN team of Mercy Corps, Indonesia provided key resources and guidance as I investigated institutional knowledge exchange in Jakarta, and I am particularly indebted to Aniessa, Ratri, Yoga, Iman, Fanni, and Farraz. I want to thank my advisor Amity Doolittle and my colleagues Sarah, Yan, and Amber for their tireless insight throughout the writing process. I also want to thank Ewin Winata, who helped translate this abstract. Lastly, none of the research would be possible without the love and support of my parents and my sister Michelle.

References

Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ Environmentally Sustainable Cities (ASEAN ESC). 2011. Indonesia’s First National Steering Committee Meeting. Retrieved from: http://aseanmodelcities.org/news/indonesias-1st-national-steering-commit…. Accessed: 2016-11-24

Damanhuri, E., Handoko, W., & Padmi, T. 2014. Municipal solid waste management in Indonesia. In: Pariatamby, A. & Tanaka, M. (eds). Municipal Solid Waste Management in Asia and the Pacific Islands. Challenges and strategic solutions. 139–155. Springer-Verlag, Singapore.

Hajramurni, Andi. 2015. Garbage banks continue to flourish nationwide. The Jakarta Post. 19 Sept 2015. Retrieved from: http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/ 09/19/garbage-banks-continue-flourish-nationwide.html. Accessed: 2016- 11-25.

Harfam. 2012. Prestigious award for the clean city. Retrieved from: http://harfam.co.id/en/peng hargaan-prestisius-untuk-kota-idaman. Accessed: 2016-11-29.

Idrus, A. 2014. Kindergarten accepts garbage as school fees. The Jakarta Post. 14 Oct 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2014/ 10/14/kindergarten-accepts-garbage-school-fees.html. Accessed: 2016-11-25.

Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES). 2015. ASEAN ESC Model Cities Programme. IGES, Bangkok, Thailand. Retrieved from: http://aseanmodelcities.org/wp- content/uploads/2015/11/ModelCities_ ProgramBrochure-Nov-2015.pdf.

Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES). 2012. Overview of Year 1 ASEAN ESC Model Cities Programme. Retrieved from: http://aseanmodelcities.org/wp-content /uploads/2015/07/Overview-of-Year-1-ASEAN-ESC-Model-Cities-Programme-for-website.pdf.

Jeffery, P. 2013. Business feasibility study: Trash to cash (T2C). Bandar Lampung Waste Bank Final Report. CAC 314 Vol. ACCCRN, Jakarta, Indonesia.

King, R, & Dyah, E.I. 2010. Surabaya kampung and distorted communication. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 25, 213–33.

Lavigne, F., Wassmer, P., Gomez, C., Davies, T.A., Sri Hadmoko, D., Iskandarsyah, T. Yan W. M., Gaillard, J.C., Fort, M., Texier, P., Boun Heng, M., & Pratomo, I. 2014. The 21 February 2005, catastrophic waste avalanche at Leuwigajah dumpsite, Bandung, Indonesia. Geoenvironmental Disasters 1, 10.

Lubis, R.L. 2015. The triple drivers of ecopreneurial action for taking the recycling habits to the next level: A Case of Bandung City, Indonesia. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Thought 5, 17–48.

Maeda, T., Shom T., and Gilby, S. Indonesia Model City Activities Fact Sheet. ASEAN ESC Model Cities. Kitakyushu, Japan: IGES, 2011. Retrieved from: http://aseanmodelcities.org/wp-content /uploads/2015/07/Country-City- Fact-Sheet-27-Feb-2012-Surabaya-Palemba ng.pdf.

Meidiana, C., & Gamse, T. 2010. Development of waste management practices in Indonesia. European J. of Scientific Research 40, 199–210.

Phelps, N.A., 2014. Urban inter-referencing within and beyond a decentralized Indonesia. Cities 39, 37–49.

Prihtiyani, E. 2010. Bank Sampah Gemah Ripah. Kompas. Nov 3 2010. Retrieved from: http://megapolitan.kompas.com/read/2010/ 11/03/03105961/Bank.Sampah.Gemah.Ripah. Accessed: 2016-11-25.

Ramdhani, F., et al. 2010. Inspirasi Dari Timur Jawa: Sebuah perjalanan menuju surabaya ber sih dan hijau. Unilever, Surabaya, Indonesia.

Rosdiana, D. 2013. Green and Clean—Providing a clean and healthy environment through community participation in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Company-Community Partnerships for Health in Indonesia. Case Study. Retrieved from: http://ccphi.org/ccphidoc/study_eng/CS-UI_Persada-English.pdf.

Tahir, A., Mitsuo, Y., & Sachihiko H. 2011. Expanding the implementation of community-based waste management: Learning from the green and clean program in Indonesia. Journal of Environmental Information Science 40, 79.

Tuori, M.A. 2012. Strengthening Informal Supply Chains: The case of recycling in Bandung, Indonesia. Thesis (M. Eng. in Logistics), Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) and United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). 2015. The State of Asian and Pacific Cities 2015: Urban transformations shifting from quantity to quality. UN-Habitat and UN ESCAP. Retrieved from: http://www.unescap.org/resources/state-asian-and-pacific-cities-2015-urb… formations-shifting-quantity-quality

Unilever. 2016. Environment Programme. Uni-lever Foundation. Retrieved from: https:// www.unilever.co.id/en/about/unilever-indonesia-foundation/environment-pr… me.html.

Wijayanti, D.R., & Suryani, S. 2015. Waste bank as community-based environmental governance: A lesson learned from Surabaya. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 184, 171–179.

Winarti, Agnes. ‘Trashion’ Sets Trend for Green Campaigns. The Jakarta Post. June 25, 2008.

-

Sam Geldin is a Masters of Environmental Science candidate and studies the intersection of climate adaptation, disaster risk reduction, and international development. This essay is part of a larger report of findings he completed while conducting research in Jakarta for the Asian Cities Climate Change Resilience Network (ACCCRN), a Rockefeller Foundation program implemented by Mercy Corps. Sam received a BA in Geography and a BS in Environmental Science in 2015. Before coming to Yale F&ES, he worked for the California Governor’s Office of Planning and Research and the public-private partnership R20 to support local adaptation policies and project financing.↩

-

A best practice can be defined as a replicable action or set of principles or goals meant to reproduce similar outcomes. In practice, however, best practices can only yield “best” results in other locations for certain groups of actors, under certain conditions, and after particular implementation procedures.↩

-

Foundation representative, pers. communication, Aug. 25, 2016, Cirebon Metland Hotel.↩

-

Program manager, international NGO, pers. communication, Aug. 19, 2016.↩

-

Foundation representative, pers. communication, Aug. 26, 2016.↩

-

Local NGO representative, pers. communication, Aug. 20, 2016, Kota Karang Waste Bank, Bandar Lampung.↩

-

Foundation representative, pers. communication, Aug. 26, 2016.↩

-

Project manager, international NGO, pers. communication, Aug. 12, 2016, Mercy Corps Offices, Jakarta.↩

-

Foundation representative, pers. communication, Aug. 26, 2016.↩

-

Foundation representative, pers. communication, Aug. 26, 2016.↩

-

Foundation representative, pers. communication, Aug. 26, 2016.↩

-

Foundation representative, pers. communication, Aug. 25, 2016, Cirebon Metland Hotel.↩

-

Program manager, international NGO, pers. communication, Aug. 19, 2016.↩

-

Foundation representative, pers. communication, Aug. 25, 2016, Cirebon Metland Hotel.↩