The Heirloom Rice Project: Rural transformation in the rice terrace landscapes of Ifugao and Mountain Province, Philippines

The Heirloom Rice Project: Rural transformation in the rice terrace landscapes of Ifugao and Mountain Province, Philippines

Adrien Salazar, MEM1

While the outward appearance of the agricultural landscape in the broader central valleys has probably retained its general form throughout the historic period, any resemblance to a static and unchanging permanent sculpture or construction is misleading. Only by constant repair, extension, restructuring, and the dynamic recycling of resources has the present landscape been achieved and maintained … all available cultural and environmental evidence indicates that the contemporary form of land use in Ifugao was developed in small increments by the forebears of the present inhabitants, over a period of many centuries, within this and adjacent regions of northern Luzon.

From Ethnographic Atlas of Ifugao, 1980. Harold Conklin, April 27, 1926–February 18, 2016.

Introduction

In landscapes all over the world, communities have developed complex resource management and production systems that have enabled them to sustain livelihoods in their local environments for generations. These systems tend to employ multiple land-uses, a diversity of crop varieties and species, and traditional technologies that have co-evolved with the societies that steward these landscapes and resources. In these socio-ecological systems (SES), communities utilize diverse technologies, knowledge, and management structures to produce food, fodder, and fiber to support their livelihoods, steward ecosystems and local biodiversity.

Many of these production systems are maintained today in rural and frontier landscapes that are undergoing transformation due to various forces. Formerly remote communities are increasingly connected to regional, national, and international markets. Traditional systems and technology compete with industrial food production and resource extraction. Communities seek economic development and diversified sources of income. Yet as some aspects of the human-environment relations that have shaped these systems transform over time, other elements endure.

The rice terraces of the Cordillera Mountains region of the Philippines, developed and managed by dozens of ethno-linguistically distinct indigenous peoples, are such a landscape system constituted by multiple land-uses, diversified crop production, and traditional governance systems (Acabado 2014, Araral 2013, Camacho et al. 2012, Conklin et al. 1980, , Crisologo-Mendoza & Prill-Brett 2009, De Raedt 1987, Eder 1982, Nozawa et al. 2008). Farmers in these communities engage in private and communal forest management, swidden agriculture, and rice production in centuries-old terrace and irrigation systems that take advantage of the mountainous tropical terrain (Acabado 2014, Nozawa et al. 2008, Conklin et al. 1980). The peoples of the region have built and maintained these systems for hundreds of years through intensive management, cultural practices, and labor arrangements that imbue the landscape with spiritual and social meanings (Conklin et al. 1980).

The microclimate of this mountain landscape and farmers’ own tastes have resulted in over 500 locally-adapted rice varieties, most of which are grown for subsistence (Nozawa et al. 2008). For many farmers, their native rice is a source of sustenance and serves as a living connection to ancestral practices. This landscape is globally recognized for its cultural, ecological, and architectural value, having been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Cultural Landscape in 1995, the third site to receive designation and the first to receive such as an “organically evolved landscape” (Rössler 2006).

The Cordillera Rice Terraces (CRT), like most rural frontier landscapes around the world, face a host of internal and external pressures reshaping the landscape and the societies that depend on it. The rice terrace socio-ecological system continues to evolve in response to bio-physical and socioeconomic forces of change. Traditional diversified agricultural systems confront pressures to produce more food for growing populations, increased connectivity to markets, urbanization, and development. Such pressures encourage homogenization of land-use in traditionally mosaic landscapes, and use of chemical inputs that degrade agroecosystems (Biodiversity International 2014, Koohafkan & Cruz 2011). In addition to regular risks smallholder farmers face such as pests, crop disease, lack of access to farm capital, and weather variability, farmers also adapt their production and land-use strategies to cope with increasingly degraded terrace infrastructure, extreme weather, and reduced household labor due to migration and increased off-farm income opportunity (Bantayan et al. 2012, Eder 1982, Gomez & Pacardo 2005, Ngidlo 2011, 2013a,b). These forces influence farmers’ land-use choices and in turn shape the biophysical face of the landscape.

Development efforts in the region have attempted to help conserve the form and practices of the CRT landscape, repair damaged rice terraces, as well as improve farmer livelihoods. The Heirloom Rice Project (HRP) entered this region as one intervention attempting to conserve traditional heirloom rice and promote economic opportunity for farmers. Launched in 2014, the HRP was an agricultural development project funded by the International Fund for Agriculture and Development and the Philippines Department of Agriculture, implemented by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and the Philippine Rice Research Institute (PhilRice) in collaboration with local government units, universities, and NGOs. The primary aims of the project were to characterize and conserve the diversity of native, or ‘heirloom’, rice varieties, improve farmer organizational and business capacity, and develop markets for these distinct rice varieties (IRRI 2014, Cruz et al. 2014).2

Through a mix of strategies, the project aimed to create favorable market conditions for heirloom rice in order to improve farmer income potential from this rice. The project engaged scientific characterization and development of traditional rice varieties, market research, enhancement of farmer production techniques, and obtaining of geographic indication for locally-sourced rice varieties. These strategies together aimed to create greater incentives for farmers to maintain and develop rice varieties on their lands as a counter-weight to forces that threaten the integrity of these landscapes. The project thus proposed conservation of heirloom rice and farmer income opportunities derived from improved heirloom rice production as one solution to conservation of the CRT.

Change and vulnerability in the Cordillera Rice Terrace landscape

Biophysical, social, and cultural change in Cordillera Rice Terrace systems are well documented in literature about this landscape (Bantayan et al. 2012, Eder 1982, Gomez & Pacardo 2005, Ngidlo 2013a,b). Assessing farmers’ perceptions of change and vulnerability can complement such analyses. Identifying farmers’ perceptions of vulnerability can help reveal salient pressures that inform farmer’s decisions. This information in turn can inform decisions about the type of interventions farmers desire.

This report summarizes research conducted from June–August 2015, in the second year of the IRRI Heirloom Rice Project, at three project sites: Hapao in Ifugao Province, and Barlig and Kadaclan in Mountain Province. Through analysis of project documents, participant observation, and interviews conducted with project stakeholders, this study characterizes the perceptions of transformation in this landscape.

Characterizing change in this landscape and the way the project intervenes in an ongoing process of rural transformation can provide valuable insight into whether and how agricultural development projects can 1) address vulnerability of farmers and 2) help conserve traditional agricultural systems and landscapes at risk.

Change, vulnerability, and resilience in socio-ecological systems

A substantial body of literature conceptualizes the dynamics of coupled social systems and environmental systems, or social-ecological systems (SES) (Berkes et al. 2000, 2008, Folke 2006, Olsson et al. 2004, Turner et al. 2003, Holmes 2001, Walker et al. 2006). These analyses emphasize the interconnected social and ecological dimensions of natural resource management systems, their ability to withstand change, and to transform (Folke et al. 2005).

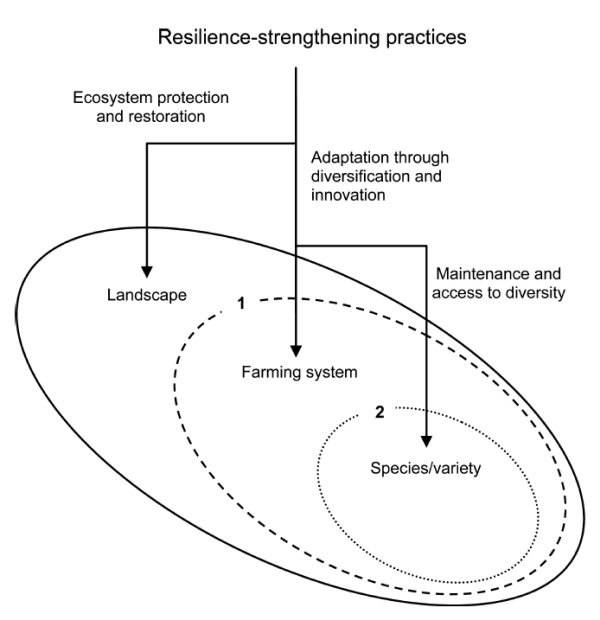

Characterizing change and resilience in SES can be a daunting task as these landscapes take diverse forms all over the world (Walker et al. 2004). Attempts to develop measures of resilience for agro-ecological systems and traditional landscapes have focused on identifying bundles of ecological, agricultural, cultural, and socio-economic indicators that contribute to functions of the system (Bergamini et al. 2013, Biodiversity International 2014, Mijatovic et al. 1993). Recognizing multiple scales—crop species and variety scale, field and farm scale, and landscape scales—of productive systems surfaces dynamics between individual farmer crop and land-use choices, social networks, and agro-ecosystems (Mijatovic et al. 2010) (Fig. 1).

Past descriptions of the Cordillera Rice Terraces have drawn from the rich ethnographic body of study of Cordillera communities and their resource management systems, and studies documenting the biophysical dynamics of the rice terrace agro-ecological systems (Conklin et al. 1980, Kwiatkowski 2013, Nozawa et al. 2008). However few studies of the CRT have analyzed rural change within a framework of vulnerability and resilience of farmers and landscapes. This study describes perceptions of vulnerability and change at three HRP project sites. The analysis draws from interviews and observations describing farmer perceptions of their own vulnerabilities and needs. Understanding processes of change, vulnerability, and resilience in the CRT landscape is useful to accurately identify social, economic, and biophysical factors that can be leveraged to promote conservation of the wealth of cultural heritage, knowledge, and agro-ecological functions of these systems.

Characterizing rural transformation and change

Over the last several decades scholars of multiple disciplines have described rural transformation as a process of transition from subsistence to commercial agriculture, of mechanization, commoditization, and out-migration (Gibson et al. 2010, Mertz et al. 2005, Pingali 1987). Scholars have documented landscape change in the form of degradation, land-use change, and the persistence of traditional management strategies (Mertz et al. 2005). Markets are a strong force of change, but are not the only factor in rural transformation.

Gibson et al (2010) have suggested that this discourse has had a ‘performative effect’ on how agricultural development practitioners characterize rural change and the types of interventions they engage (Gibson et al. 2010). While some rural economies have undergone transitions driven by processes of industrialization and globalization, this linear model of change is limited in its capacity to describe transformation in rural societies.

Changing ecological, demographic, and socio-political conditions in agricultural economies, have resulted in transformations in state power, connectivity to global processes, and changes in livelihood and income sources for farming communities (Mertz et al. 2005). Farmers engage various responses to political and economic change, such as adoption of new production practices, cash crops, intensification or dis-intensification of land-uses, engagement with markets, expansion of livelihood strategies, or maintenance of traditional practices (Mertz et al. 2005). Farmers do not necessarily resist development, and in many cases also continue to maintain traditional practices not only for livelihood benefits, but at times because these practices are central to cultural identity and social structures (Cramb et al. 2009).

The representation of rural change as unidirectional transformation towards intensification, mechanization, and urbanization—in effect, de-ruralization—fails to capture the range of strategies farmers engage in response to social, economic, and political change. Gibson et al (2010) argue that this discourse naturalizes the classic economic development pathway of capitalist modernization, neglecting the diversity of economic practices farmers engage, the presence of the non-agricultural in the rural context, and global connections that do not necessarily produce de-ruralizing consequences. This produces a “guiding dynamic” of capitalist development, obscuring variation and heterogeneity of rural transformation (Koppel et al. 1994).

Alternative models of rural transformation have attempted to capture the breadth of forces influencing change in rural landscapes. The sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF) expanded notions of livelihood practices of rural households beyond farm and land-focused definitions of rurality (Chambers & Conway 1992, Ellis 1998, Scoones 1998). SLF scholars “took up the task of developing a new language of the rural, drawing upon ecological representations of diversity, complexity, sustainability, resilience and vulnerability” (Gibson et al. 2010). Scholars drew on the ecological resilience literature and applied them to socio-economic contexts, emphasizing for example the significance of complexity and diversity in livelihood strategies in enhancing resilience (Adger2000, Chambers & Conway 1992, Scoones 1998).

This discourse shifted development strategies towards livelihood diversification, with an emphasis on understanding vulnerability in rural contexts in terms of five capitals—natural, physical, financial, human, and social. However, in practice, diversification strategies have moved towards economic outputs as measures of development, returning to a representation of rural transformation as an inescapable march towards economic development.

Alternatively, Jacobs (2000) has suggested rural socio-economic systems exhibit complex dynamics of natural ecosystems, for example habitat maintenance, diversity, resilience, interdependence of developments, and co-developments. Analyses such as these create wider space for representing rural dynamics in ways that embody the diversity of processes that constitute complex SES. An analysis of complex dynamics and simultaneous transformative effects occurring concurrently at different scales and timeframes can illuminate farmers’ production decisions and livelihood strategies, and inform the aims of development interventions like the HRP a in an evolving landscape.

Methods

This study attempts to characterize the rice terrace landscape in three sites of the HRP. The study utilizes a diversity of methods to assess perceptions of change and farmer priorities for intervention outcomes. I conducted a review of the literature on the CRT to assess how previous scholarship has characterized vulnerability and change in the landscape. I reviewed project documents including official project reports to identify the HRP intervention logical framework. I conducted participant observation during HRP activities, semi-structured and unstructured interviews with 36 project implementers, partners, and farmer-beneficiaries.

Through analysis of literature, participant observation, and interviews, I identified processes of transformation in the rice terrace landscapes of Hapao and Barlig, salient for HRP actors. I analyzed the causal linkages between perceived social, economic, cultural, environmental, and historical changes to theorize processes of transformation occurring in these communities. I also identified threats and vulnerabilities that farmers expressed as their greatest concerns in the maintenance of their livelihoods and culture.

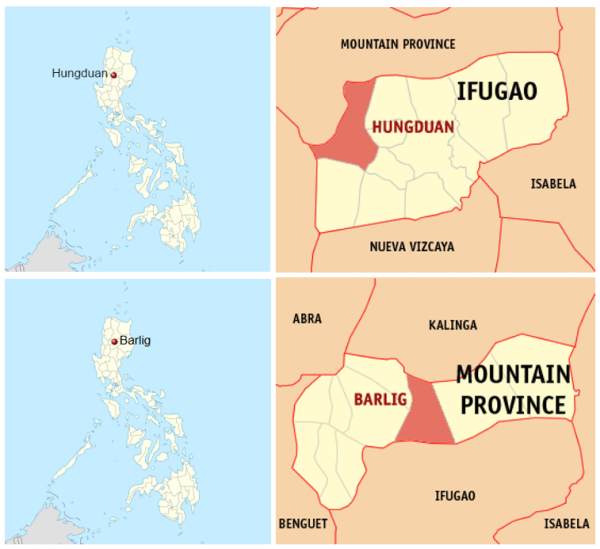

I conducted farmer interviews at two project sites: Barangay Hapao, Hungduan, Ifugao and Barangay Barlig Centro, Barlig, Mountain Province (Fig. 2). I developed a list of 49 indicators based on the views expressed by farmers I had interviewed and implemented an indicator scoring workshop among farmer organization members in two sites: Barangays Kadaclan and Barlig Centro in Barlig, Mountain Province. The results of the indicator assessment are not presented in this paper.

Site description

The Heirloom Rice Project has fifteen sites across four provinces of the Cordillera region—Ifugao, Mountain Province, Kalinga, and Benguet. The objectives of the project are to conserve heirloom rice varieties, improve farm productivity, enhance capacity for farm enterprise, and identify market opportunities for heirloom rice. The project engaged farmer associations and cooperatives, local government units such as municipal departments of agriculture, and local universities and colleges. HRP activities included needs assessment, visioning activities, rice identification, varietal trial plots, disease tests, and extension workshops.

Hapao, Ifugao.—Hapao, a barangay (submunicipal or village government unit) is part of the municipality of Hungduan, in Ifugao Province (Fig. 2). Hapao has a population of 2,138, or 21% of the total population of Hungduan as of 2015 (National Statistical Coordination Board, Philippines). The land area of Hungduan is 23,131 ha, of which the municipality classifies 11,403 ha (48%) as forest, 6,876 ha (30%) as grassland, and 705 ha (3%) as agricultural. Rice terraces in the municipality are classified as part of the World Heritage Site cluster of rice terraces in Ifugao Province. Hapao is 1,677 ha and municipal figures designate 160 ha as rice terraces, however community-based mapping has identified 555 ha of rice terrace area in the barangay (Bantayan et al. 2012).

I conducted semi-structured interviews with members of the Hapao Farmers Association (HFA), the HRP farmer-beneficiary group of Hapao. This association was established in 2006 as one of the initial members of a regional cooperative, the Rice Terraces Farmers Cooperative, based in Banaue, Ifugao. The HFA has 62 member farmers of which 58 (93%) are women. Farming is the primary source of livelihood for residents of Hapao. They grow a number of rice varieties. Some varieties identified by the HRP include tinawon, minaangan, uklan, and umbuukan. The rice production calendar begins in October or November with harvest taking place from June-August. Interviews were collected in July 2015 during the peak of the harvest season, which posed some selection bias for farmers who had flexibility to participate in the study during this demanding period. Interviews were conducted in English, with translation support in Ifugao provided by an assistant who was a resident of Hapao.

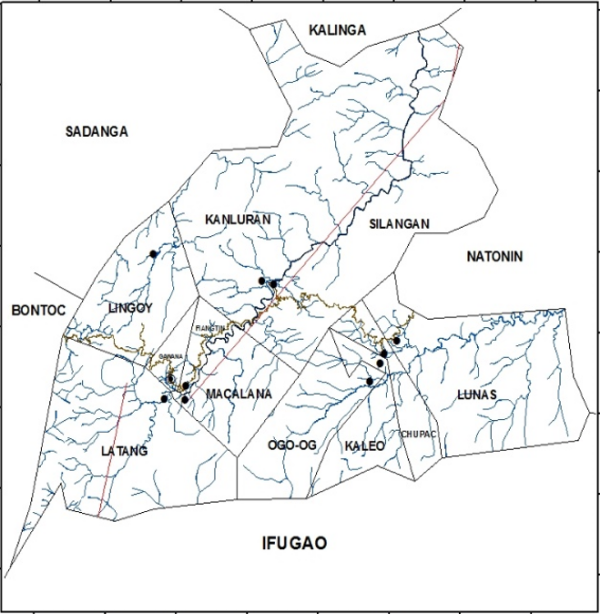

Barlig, Mountain Province.—In Barlig, two groups were consulted: the Barlig Heirloom Rice Organization (HRO) and the Kadaclan Heirloom Rice Organization. Both groups are located in the municipality of Barlig in Mountain Province, Philippines, but each encompasses a distinct ethno-linguistic peoples and geographic areas—the Barlig and the Kadaclan clusters of barangays in Barlig municipality, respectively (Figs. 2 and 3). Barlig municipality covers a range of 1000-2862 m above sea level and is characterized by pine and oak forest, rice fields, and swamps, with approximately 73% (26281 ha) of the total land area in forest and 5.33% (1921 ha) in agriculture (Municipal Planning and Development Office, Barlig, 2002). Of 1425.7 ha in crop production in 2002, 1118 ha were in rice production (Municipal Planning and Development Office, Barlig, 2002). The total population of the municipality was 5838 in 2010 (Municipal Planning and Development Office, Barlig, 2015), constituted mostly by three ethno-linguistic groups—the I-Kachakran, I-Lias, and I-Fiallig peoples. Interviews and workshop activities were conducted in late July and early August, during the harvest season. Interviews were conducted in English by the author with translation support from Municipal Agriculturalist Office staff.

The Kadaclan HRO was founded in 2008 via the support of the NGO RICE Inc., and has 71 members covering the barangays of Chupac, Lunas, Kaleo, and Ogo-og. This farmer group specializes primarily in the production of the ominio rice variety for subsistence and for export, but farmers grow a number of other varieties for subsistence consumption. The Barlig HRO began in 2013 via the support of RICE Inc. and the Office of the Municipal Agriculturalist (OMAg). Barlig HRO covers the most populous cluster of barangays of Barlig, with members from Barangays Gawana and Latang. Barlig HRO currently has 30 members producing a number of rice varieties for market including chanannay, kulii, engoppor, and chorchor-os varieties. The formal involvement of these organizations in the IRRI HRP has included engagement in planning processes with project partners including OMAg, the Department of Agriculture regional office, and local universities. The farmers groups have also participated in a number of extension trainings facilitated by OMAg and PhilRice for the HRP.

Results

Farmers vulnerabilities in the face of change in the Rice Terraces

Review of project documentation, interviews with project implementers, and participant observation reveals that Heirloom Rice Project implementers framed the project around perceived vulnerabilities at the crop variety and farmer household scale. The project was framed around two objectives: conservation of genetic resources and economic development. The project identified market and product development as a means to encourage farmers to grow heirloom varieties, some of which may be “threatened genetic resources”. Productivity improvements, business capacity, and market linkages were causally suggested to help conserve rice varieties while increasing income for farmers. Program proponents suggested that increasing conservation of rice varieties and improving income from heirloom rice would promote the long-term conservation of traditional rice production in the CRT landscape.

The HRP identified sites as “resource poor areas rich in agrobiodiversity” where a number of productive limitations and limited market access reduced farmers’ ability to generate income from their traditional rice. Project documentation also referred to conservation of “climate resilient rice varieties” and the ability of genetic diversity to provide farmers capacity to cope with climate change. Project implementers also suggested that the project would help protect and conserve the culture of the indigenous communities who manage the rice terraces. Thus the project aimed to address key vulnerabilities of: 1) lack of productive capital for rice production, 2) limited income opportunity, 3) risk of loss of genetic diversity, 4) risk of cultural loss, and 5) climate change risks.

The economic development and agrobiodiversity conservation focus of the project influenced the way activities with farmers were framed. Activities were oriented towards scientific identification of varieties and production-enhancement.

In a participatory needs-assessment conducted for three Ifugao Province sites including Hapao, farmers identified problems and areas of need. Nearly all of these were production-oriented challenges. The HRP-facilitated needs-assessment identified the main areas for improving rice production as: 1) increasing yield, 2) improving postharvest/processing and marketing, 3) provision of farmer implements and inputs, 4) capacity building, 5) infrastructure development, and 6) multipurpose environment conservation strategy. Likewise the Barlig HRO and Kadaclan HRO participatory needs-assessments were framed around issues faced in production, post-harvest, and marketing with a number of similar challenges and opportunities identified in these areas.

Interviews with farmers echoed these productive needs but revealed other areas of vulnerability. While many farmers expressed a need and desire for increased cash income and increased yields, farmers in Hapao also emphasized their concern for food security. Farmers expressed the primacy of producing rice for their household before selling any rice in the market. During interviews farmers repeatedly demonstrated that at least half of rice they grew was for their own household consumption, revealing that most heirloom rice production is subsistence-oriented. Participants generally produce sufficient amounts of rice for consumption, however some respondents suggested that other farmers are only able to produce enough rice for 4-5 months of consumption.

Farmers also expressed a number of production vulnerabilities. These include challenges in the maintenance and repair of damaged terraces, terrace abandonment, insufficient irrigation, climate risks such as typhoons and flooding, prevalence of crop pests, lack of capital and equipment, and labor limitations due to migration. These challenges are viewed as intertwined. Climate impacts such as typhoons, for example, are of primary concern for farmers in Hapao because they can result in damages to terrace infrastructure. This damage can lead to long-term reductions in yields, threatening food security. Farmers in Barlig expressed concern for threats that impact rice production including climate-based impacts on rice quality and the prevalence of pests—namely rats and earth worms—that reduce yields.

Change and robustness in the Rice Terraces Landscape

Changes observed by farmers are manifold: environmental change, agricultural change, socio-economic change, cultural change, and socio-demographic change. Certain practices and conditions have also persisted and demonstrate the robustness of some elements of the rice terrace landscape systems.

Some of the most salient changes for farmers are those agricultural changes that have transformed traditional production. Some respondents in Hapao noted that the planting calendar has shifted later in the year for many farmers. Most farmers in Hapao expressed a specific change in the variety of rice produced from the tinawon variety to the mina-angan variety within a generation due to evidenced improved yields from mina-angan rice.

In contrast, Barlig farmers tended to produce a mix of varieties in their fields. They expressed more flexibility in trading rice varieties with one another and experimenting to select rice varieties for various characteristics including yield and flavor. No specific time-scale in rice varietal changes was identified by Barlig farmers suggesting that the dynamic movement of rice varieties among Barlig farmers is an ongoing historical practice.

Hapao farmers also expressed pride in maintenance of traditional production methods, avoiding herbicide and pesticide use, while also mentioning that some technology has introduced mechanization to certain elements of production. Many Hapao farmers expressed concern for the disregard of some traditional practices including terrace restoration and irrigation maintenance. In contrast some Barlig farmers mentioned they had experimented with various technologies including chemical fertilizers, herbicide, and mechanized equipment to aid in maintenance of their fields.

Key observed changes in the rural economy include monetization (entry into cash economies), development of infrastructure, and increased connectivity to regional and global economies. The communities in Ifugao have historically organized their economies around rice production for subsistence. However increased integration into national and international markets has introduced the necessity for cash income and diversified sources of livelihood. Local development of roads, electricity, and other infrastructure have improved connectivity of the region, and tourism has brought in some development.

Some traditional labor arrangements have been influenced by economic transformations as well. The traditional communal irrigation management of Hapao has declined as farmers observe that irrigation repair is increasingly viewed as a responsibility of the state. Volunteer labor or labor in exchange for rice has been replaced by labor for cash. However ubbu, or communal harvesting, continues to persist in Hapao. Many families also have members who have migrated to cities or outside the country, who work and send remittances to their families.

Farmers also observed transformations on the physical landscape due to coupled environmental and social forces. Hapao farmers note degraded infrastructure and damage to rice terraces, the presence of pests and disease, and the impacts of climate as key forces. Farmers in both Hapao and Barlig perceive a greater prevalence of damage to terrace infrastructure, which generally is linked to flooding from weather events. However farmers expressed that they do not perceive weather events as any worse or more intense as in the past. Rather the prevalence of terrace damage is perceived as a result of “abandonment” due to labor constraints on repairs. Barlig farmers expressed concern over abandonment of rice fields as well as over the conversion of rice fields to vegetable production—viewed as a departure from the appropriate use of the terraces. Farmers who convert some portion of their fields for vegetable production did so as an alternative use of damaged terraces, to produce additional food for home consumption or for sale.

Cultural transformation is an ongoing process in the region. Rice production is historically highly ritualized. In Ifugao province this has meant production involved the engagement of mumbaki, spiritual knowledge-holders who facilitate ritual at various stages of rice production. Hapao farmers suggested that fewer and fewer people practice the traditional rituals because there are fewer mumbaki remaining, and many farmers have converted to Christianity. In Barlig, none of the farmers interviewed practiced traditional rituals associated with production. Elder farmers interviewed recalled practices from their youth but mentioned that these practices diminished by the time they were adults, as traditional practitioners passed. The vast majority (84.1%) of residents of Barlig identify as some Christian denomination.

Farmers are also concerned about conservation of their culture in a general sense, as young people are sent out for education and work, not returning to farm work. This movement of people out of the region was cited frequently by farmers as a labor constraint. Fewer people remained to manage the terraces and help in rice production. This also disrupted traditional practices of inheritance. In Ifugao province, rules of inheritance have traditionally prevented rice terrace land from being divided among children (Araral 2013). Eldest children typically inherited entirety of rice terraces. However, today this practice is inconsistent and those who tend the terraces are the family members who choose to remain in the countryside.

Discussion

This research project combines a mix of methodologies in order to describe the perceived vulnerabilities farmers and to characterize the nature of rural transformation in two HRP project sites. The following sections summarize the context of change at the sites and highlight some of ways the HRP aligns with or misses some of the areas of concern revealed by the analysis.

Rural transformation in the Cordillera Rice Terrace landscape

For a project like the HRP, understanding the dynamics of ongoing transformation, vulnerability, and resilience is key for developing interventions that address threats to the integrity of landscapes while meeting the needs of community members who steward them. This study revealed that the farmer communities of Hapao and Barlig not only face numerous rice production constraints and a desire for greater economic opportunity, but that these constraints arise out of processes of socio-economic and cultural transformation occurring in these communities at multiple scales.

For farming communities in Barlig and Hapao, a number of push and pull factors influence farmer production choices. This study demonstrates that the desire for improved production is a salient concern among farmers. For many, however the first imperative for improved production is food security rather than income from their heirloom rice. Farmers are also concerned about infrastructural integrity of their terraces and lack of upkeep across the landscape leading to terrace abandonment. Conservation of traditional cultural value systems is also a key concern for these communities.

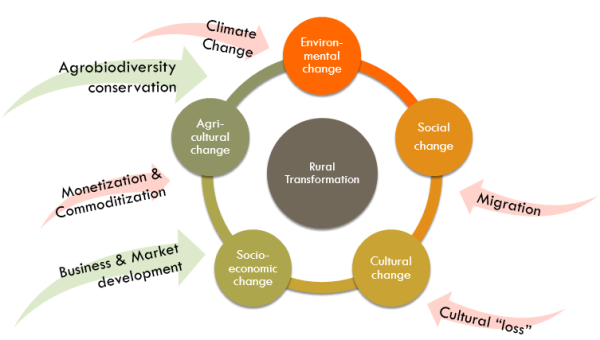

Farmer and landscape vulnerability that arises from these issues occurs at multiple scales. For example farmers make seed and variety choices at the field and farm household scale, but issues such as cultural loss, labor constraints, and outmigration are processes that occur at the community, regional, and even international scales. Some of these processes may also appear at odds with one another—for some farmers the desire to maintain traditional cultural practices may conflict with the desire for increased productivity. However this tension demonstrates that farmers in the CRT are able to engage a diversity of practices and strategies in response to the change and vulnerability they face. For the HRP, which focuses on farmer households and farmer self-help groups as the scalar unit, this means a holistic consideration of these dynamic processes (Fig. 4) and integration of other strategies at multiple scales, perhaps engaged by other partners, can help address some of these salient concerns beyond farm productivity. While agricultural development projects may be limited in their scope by necessity, this project highlights the challenges of a linear-development-driven understanding of rural transformation. While agricultural development projects may be limited in their scope by necessity, this project highlights the challenges of a linear-development-driven understanding of rural transformation.

The rice terrace landscapes of Hapao and Barlig are being transformed by a host of processes of change. Agricultural production transformations such as shifts in rice varieties and transitions away from traditional production processes are shaped by farmers’ preferences for improving yields with appropriate technologies. Farmers face the biophysical forces, like climate change, which map onto the landscape in the form of damaged and degraded terrace infrastructure. Cultural transformations such as declining practice of traditional labor arrangements and demographic shifts due to migration limit the labor capacity of farmer households to maintain their terraces, as socio-economic integration transforms farmers’ relationships to cash economies. As Christianization and cultural norms influence farmer’s choices to engage in traditional rituals, traditional knowledge and practices are at risk of disappearing from the landscape.

Additionally while some elements of the SES undergo transformation, certain elements persist, disrupting the narrative of linear unidirectional development. What persists and what transforms can vary from one community to another. For example, varietal choices can change rapidly in an environment where farmers grow multiple varieties in the same field, as in Barlig, however in Hapao, farmers have grown primarily the same varieties due to consistent yields.

A model of change that is more representative of interactions between processes and across scales would account for these multiple transformations. What farmers want and need from agricultural and development interventions is thus shaped by a complex matrix of factors including desire to conserve a landscape and culture, desire for increased economic opportunity, desire for food security and subsistence, and desire for cash income. An intervention like the HRP attempts to impress upon a changing SES a certain kind of transformation, in a certain direction, what Koppel and colleagues call a “guiding force” of capitalist development (Koppel et al. 1994).

This linear model of change obscures the diversity of transformations actually taking place in rural landscapes. The success of such interventions will remain limited at best, and may even have unforeseen negative consequences such as increasing risk of cultural loss, if the logical frameworks fail to recognize feedbacks, scalar processes, and interdependence.

A different model of change that accounts for complexity, diversity, and interdependence, across scales, may enable such development projects to more accurately assess the forms of rural transformation taking place in key areas at risk. Alternative frameworks for understanding transformation, such as an ecological understanding of interdependent developments and diversity of livelihoods proposed by Jacobs (2000) can be useful for more accurately assessing where interventions are or are not addressing key SES vulnerabilities (Jacobs 2010). In the case of the HRP such an analysis reveals that while the project acknowledges key processes in agricultural and socio-economic transformations, it may fail to adequately address environmental, socio-cultural, and demographic transformations that are intertwined and complicating the former.

Ultimately this analysis of rural transformation can help create a richer picture that can inform how interventions like the HRP position their activities in relation to processes of change already occurring in these communities, with sensitivity to those changes of greatest concern to the target population.

Conclusion

The Heirloom Rice Project represents an articulation of agricultural development that links agro-biodiversity conservation with farmer business and organization capacity development in the Cordillera Rice Terraces. The project aimed to address key vulnerabilities including income opportunities for farmers, limited access to productive capital, risk of biodiversity loss, and climate change.

In a landscape that faces a myriad of transformative forces the HRP suggested development of heirloom rice and markets would increase farmer incomes and thereby promote agrobiodiversity conservation, economic development, and ultimately conservation of “at risk” rice varieties and the terrace landscape broadly. However multiple processes at various scales beyond the field and farmer households shape the needs and vulnerabilities farmers face. Farmers expressed a range of perceived risks and vulnerabilities, some of which were addressed by the project. They expressed repeatedly the desire to maintain food security, exhibited by a lack of willingness to sell rice if it meant that they would not have enough of their own preferred varieties to feed their families. Farmers clearly expressed a desire for increased yields and income, and for productive enhancements such as pest management solutions and farm capital—all of which were major components of the project. Farmers also expressed key concerns about the maintenance of terrace infrastructure. These included fear of abandonment of rice terraces, attributed to loss of labor capacity due to outmigration, and erosion and damage due to weather impacts, which remained unrepaired due to the labor requirements of infrastructure repairs. Conservation of traditional cultural practices and values were also salient concerns that farmers connected directly to the maintenance of traditional rice production.

Additionally, farmer’s environmental concerns related to climate change did not necessarily align with the project strategy of agrobiodiversity conservation. While the project couched agrobiodiversity conservation within the language of building resilience to climate change, there were no project activities that addressed the climate vulnerabilities of greatest concern for farmers—infrastructural damage due to storms and flooding. The project also does not engage some of the socio-economic push-pull factors that have shaped farmer constraints on labor capacity, such as migration. Finally while the project indirectly suggested that conservation of heirloom rice would help conserve the socio-cultural systems of the SES, the project engaged no explicit cultural conservation activities such as cultural education or documentation of traditional knowledge.

The project did produce some material benefits to farmers, some of which were immediate, such as access to equipment and extension services, but the HRP was limited in its capacity to address pervasive vulnerabilities in the social-ecological system. The key challenges of a time and budget-constrained development project like the HRP in addressing a complex arrangement of forces are accurately recognizing the complexity of transformative processes in a rural landscape and delineating the scope of the project to address priority vulnerabilities in the SES. The HRP scale of interventions was the crop varietal and farmer household levels. However processes influencing crop choices and farmer livelihood strategies extended beyond these scales. Tools like the SEPLS Resilience Toolkit—which enable communities to identify bundles of indicators of landscape resilience—expand the scale of analysis and could enable a broader understanding of change in the CRT landscape (Biodiversity International 2014).

The specter of linear development in rural transformation posits that rural landscapes like the CRT are undergoing a transformation from subsistence to commercial crop production. However a complexity of forces allow both subsistence livelihoods and elements of traditional agricultural production to persist, all while farmers increasingly engage in economic networks from the local to the global scale that influence labor and land-use choices. These dynamics demonstrate a more nuanced version of rural transformation taking place in the rice terraces. The HRP assumed that biodiversity conservation and economic development could mitigate a number of risks to the SES and conserve the landscape. However given the diversity of forces, some of which are not within the scope of the project, the capacity of the project to conserve cultural systems and mitigate climate change risks appears limited. The project may be able to conserve specific rice varieties and improve incomes, a staple expertise of the International Rice Research Institute, but this may not be sufficient to protect and conserve these landscapes.

Incorporating a broader systems analysis that acknowledges the breadth of interconnected processes of transformation and change in the landscape can provide a more accurate and causally-driven analysis of vulnerability in the rice terrace landscape. Models that include feedbacks between these processes and scalar considerations can provide insight into what factors influence farmers’ land-use decisions and livelihood practices. Defining what resilience means in this landscape by using existing tools and measures of landscape resilience can help identify the suite of variables that interventions like the HRP ought to engage to: encourage conservation of cultural knowledge and traditional systems, integrate new technologies and livelihood strategies appropriately to meet farmer needs, and conserve elements that have allowed these landscapes to endure for centuries.

This study suggests that: 1) expanding the problem definition of rural development projects to address multiple processes influencing rural transformation, 2) considering multiple scales, and 3) including farmers’ perceptions of their own vulnerabilities can allow interventions like the Heirloom Rice Project to engage economic development, agro-biodiversity conservation, cultural conservation, and landscape conservation with an integrated strategy and more effective participation of stakeholders.

Heirloom rice production, like many traditional agricultural practices around the world, is often not viewed by farmers as simply an economic activity but also socio-cultural and ecological. As such, economically-driven agricultural interventions should also integrate these factors to conserve the knowledge and practices that maintain the resilience of social-ecological systems. Doing so addresses the nature of rural transformation as a complex dynamic process—a process of processes. Integrating multiple strategies and working with diverse partners to this end could prove to be an effective means to improving the livelihood of farmers and securing the integrity of these changing landscapes for generations.

Recommendations for agricultural development and landscape conservation

1. Future interventions in this region and similar interventions around the world can conduct vulnerability and threats assessments as part of participatory needs and opportunity assessment, to identify causal pathways that lead to farmer and landscape vulnerability

This study has addressed farmer vulnerability explicitly as a key motivation for agricultural and rural development. However vulnerability analysis is often not included as part of interventions, as in the case of the HRP. The analysis in this study has revealed multiple processes that produce various vulnerabilities for farmers and the landscape. Conducting a broader vulnerability assessment that identifies key threats beyond economic livelihood and agrobiodiversity threats—for example, food insecurity, cultural loss, and landscape change—and that identifies the causal pathways of these threats can reveal a more accurate picture of farmer needs and severity of threats. This can inform decisions about activities that intervene at key intersections of change and can help identify opportunities to integrate strategies that offer co-benefits.

2. Expand the project scope and scale beyond the farmer household and farmer self-help group

Assess landscape-scale dynamics and regional, national, and international scale processes and identify feasible points of intervention. The scale of challenges faced by the communities of Hapao and Barlig reveal processes extending beyond the household or barangay. Processes of increasing regional connectivity and migration influence income opportunity and migration, and shape labor constraints for rice production. While one project may not be able to address all threats at all scales, development actors can consider the influence of large-scale processes on farmer household choices in identifying scale-appropriate interventions. Farmer trainings can be supplemented with community development activities at the municipal level, or policy and management at the regional scale, for example. Integration of strategies at multiple scales, with the engagement of partner NGOs and agencies that have capacity to address some processes outside the scope of any given project, can address some of the larger push-pull factors that influence farmer decisions.

3. Activities should be developed, with the HRP or in collaboration with knowledgeable and well-capacitated partners, to explicitly address landscape infrastructure, conservation goals, and cultural conservation

Terrace damage due to storms and flooding and limited farmer capacity for repair were threats that surfaced across sites and across the multiple methodologies of this study. Cultural loss was also a significant concern for communities in which rice production is embedded in traditional social arrangements and ritual practices. While the HRP suggests heirloom rice conservation can conserve rice terraces and the culture of these communities, the project does not explicitly engage in infrastructure improvements or cultural conservation activities. These areas must be addressed to maintain the long-term integrity of the social-ecological landscapes of the rice terraces. Development actors can consider integration of diverse activities across issue areas, or develop partnerships with institutions that hold different expertise and capacity, to integrate agricultural development, biodiversity conservation, and education into a broader strategy for landscape and cultural conservation.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the International Rice Research Institute, in particular Digna Manzanilla, Casiana Vera Cruz, Aileen Lapitan, and all the staff of the Heirloom Rice Project for sharing their time and resources with me for this study. This research would not have been possible without their welcoming support. This research was also made possible by the support of the Charles Kao Fund, CocaCola World Fund, and Yale Tropical Resources Institute.

I also thank Amity Doolittle, Michael Dove, Jonathan Reuning-Scherer, and Alark Saxena for their feedback and valuable contributions to the development of this study. I especially acknowledge the late Harold Conklin, who devoted his life to the understanding and improvement of communities in the Cordillera region, across the Philippines and Southeast Asia. My deepest gratitude goes to the heirloom rice farmers and communities of Hapao, Barlig, and Kadaclan, especially those who supported me as hosts, guides, translators, and research assistants. Thank you for your hospitality, generosity, and invaluable contributions to this study.

References

Acabado, S. 2014. Landscapes and the archaeology of the Ifugao agricultural terraces: Establishing antiquity and social organisation. Hukay 15, 31–61.

Adger, W.N. 2000. Social and ecological resilience: are they related? Progress in Human Geography 24, 347–364.

Araral, E. 2013. What makes socio-ecological systems robust? An institutional analysis of the 2,000 year-old Ifugao society. Human Ecology 41, 859–870.

Bantayan, N.C., et al. 2012. Estimating the extent and damage of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites of the Ifugao. Journal of Environmental Science and Management 15, 1–5.

Bergamini, N., et al. 2013. Indicators of resilience in socio-ecological production landscapes (SEPLs), UNU-IAS Policy Report, 44.

Berkes, F., J. Colding, and C. Folke. 2008. Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building resilience for complexity and change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Berkes, F., C. Folke, and J. Colding. 2000. Linking Social and Ecological Systems: Management practices and social mechanisms for building resilience. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Biodiversity International. 2014. Toolkit for the Indicators of Resilience in Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS). UNU-IAS, Biodiversity International, IGES and UNDP.

Camacho, L.D., et al. 2012. Traditional forest conservation knowledge/technologies in the Cordillera, Northern Philippines. Forest Policy and Economics 22, 3–8.

Chambers, R. and G. Conway. 1992. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century. IDS Discussion Paper 296. Institute of Development Studies. From: http://www.ids.ac.uk/publication/sustainable-rural-livelihoods-practical…

Conklin, H.C., et al. 1980. Ethnographic Atlas of Ifugao: A study of environment, culture, and society in Northern Luzon. Yale University Press, New Haven, USA.

Conklin, H.C., P. Lupaih, and M. Pinther. 1980. Ethnographic Atlas of Ifugao: A study of environment, culture, and society in northern Luzon. Yale University Press, New Haven, USA.

Cramb, R.A., et al. 2009. Swidden transformations and rural livelihoods in Southeast Asia. Human Ecology 37, 323–346.

Crisologo-Mendoza, L. and Prill-Brett, J. 2009 Communal Land Management in the Cordillera Region of the Philippines. In: Perera, J. Land and Cultural Survival. Asian Development Bank. pp 35–62.

De Raedt, J. 1987. Similarities and differences in lifestyles in the Central Cordillera of Northern Luzon (Philippines). Cordillera Studies Center, Baguio City, Philippines.

Eder, J.F. 1982. No water in the terraces: Agricultural stagnation and social change at Banaue, Ifugao. Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 10, 101–116.

Ellis, F. 1998. Livelihood diversification and sustainable rural livelihoods. In: Carney, D. (ed). Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: What contribution can we make?. Department for International Development, London, UK. pp. 53–65.

Folke, C. 2006. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social-ecological systems analyses. Global Environmental Change 16, 253–267.

Folke, C., et al. 2005. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 30, 441–473.

Gibson, K., A. Cahill, and D. McKay. 2010. Rethinking the dynamics of rural transformation: Performing different development pathways in a Philippine municipality. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 35, 237–255.

Gomez, R. and E. Pacardo. 2005. Survey of the damage in the Ifugao rice terraces and its environmental dynamics. Philippine Agricultural Scientist 88, 133–137.

Holmes, C.M. 2001. Navigating the socioecological landscape. Conservation Biology 15, 1466–1467.

International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (IPSI). Concept. 2015. The Satoyama Initiative. Accessed: May 6, 2015. Available from: http://satoyama-initiative.org/en/about/.

International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (IPSI). 2015. In Harmony with Nature. IPSI, Editor. p. 4. Accessed: May 6, 2015. Available from: http:// satoyama-initiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/IPSI_leafA4_EN.pdf

International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), The Heirloom Rice Project, Department of Agriculture, Philippines. International Rice Research Institute, Editor. 2014: Philippines.

Jacobs, J. 2001. The Nature Of Economies. Vintage Books, New York, NY, USA.

Koohafkan, P. and M.J.D. Cruz. 2011. Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems. Biodiversity and Climate Change: Achieving the 2020 Targets.

Koppel, B., J. Hawkins, and W. James. (eds). 1994. Development or Deterioration? Work in rural Asia. Lynne Riener, Boulder, CO, USA and London, UK.

Kwiatkowski, L. 2013. Globalization, environmental change, and coping strategies among the Ifugao of the Philippine Cordillera Mountains. In: Lozny, L.R. (ed), Continuity and Change in Cultural Adaptation to Mountain Environments. Studies in Human Ecology and Adaptation 7. pp. 361–378.

Mertz, O., R.L. Wadley, and A.E. Christensen. 2005. Local land use strategies in a globalizing world: Subsistence farming, cash crops and income diversification. Agricultural Systems 85, 209–215.

Mijatovic, D., et al. 1993. The role of agricultural biodiversity in strengthening resilience to climate change: Towards an analytical framework. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 11, 95–107.

Mijatovic, D., et al. 2010. The use of agrobiodiversity by indigenous and traditional agricultural communities in adapting to climate change. Platform for Agrobiodiversity Research Rome, Italy. http://www. agrobiodiversityplatform. org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/PAR-Synthesis_ low_FINAL. pdf.(Accessed April 7, 2012).

Municipal Planning and Development Office, Municipality of Barlig, Barlig, Mountain Province, Philippines. 2002. Sustainable Development Plan, Barlig, Mountain Province. Municipal Planning and Development Office, Municipality of Barlig, Barlig, Mountain Province, Philippines.

Municipal Planning and Development Office, Municipality of Barlig, Barlig, Mountain Province, Philippines. 2015. Comprehensive Land-Use Plan, Barlig, Mountain Province. Municipal Planning and Development Office, Municipality of Barlig, Barlig, Mountain Province, Philippines.

Ngidlo, R. 2011. Drivers of change, threats and barriers to the conservation of biodiversity in traditional agricultural systems. Journal of Science and Technology B 1, 675–684.

Ngidlo, R. 2013a. Assessment of climate change impacts, vulnerabilities and adaptation strategies in the traditional rice terraces of the Cordillera region, northern Philippines. Asian Journal of Science and Technology 4, 180–186.

Ngidlo, R.T. 2013b. The rice terraces of Ifugao province, northern Philippines: Current scenario, gaps and future direction. Global Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Health Sciences 2, 151–154.

Nozawa, C., et al. 2008. Evolving culture, evolving landscapes: The Philippine rice terraces. Protected Landscapes and Agrobiodiversity Values. Protected Landscapes and Seascapes 1. IUCN & GTZ.

Olsson, P., C. Folke, and F. Berkes. 2004. Adaptive comanagement for building resilience in social-ecological systems. Environmental Management 34, 75–90.

Pingali, P.L. 1987. From subsistence to commercial production systems: The transformation of Asian agriculture. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 79, 628–634.

Province: IFUGAO. National Statistical Coordination Board, Philippines. PSGC Interactive. Accessed: 11 May 2016.

Rössler, M. 2006. World heritage cultural landscapes: A UNESCO flagship programme 1992–2006. Landscape Research 31, 333–353.

Scoones, I. 1998. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: a framework for analysis. Working Paper 72, Institute of Development Studies. From: http:// www.ids.ac.uk/publication/sustainable-rural-livelihoods-a-framework-for-…

Turner, B.L., et al. 2003. Illustrating the coupled human-environment system for vulnerability analysis: Three case studies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100, 8080–8085.

Vera Cruz, C., D. Manzanilla, and R. Miranda. 2014. Progress Report of the Project “Raising Productivity and Enriching the Legacy of Heirloom/Traditional Rice through Empowering Communities in Unfavorable Rice Based Ecosystem (Heirloom Rice Project)” 01 February 2014-31 January 2015. 2015: Quezon City, Philippines.

Walker, B., et al.. 2004. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society 9, 5.

Walker, B., et al. 2006. A handful of heuristics and some propositions for understanding resilience in social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society 11.

-

Adrien Salazar holds a Master’s of Environmental Management from the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. His work focuses on resource rights, culturally-based conservation, resource management, and community engagement.↩

-

Cruz, C.V., Plant Pathologist (Senior Scientist II) at Plant Breeding, Genetics and Biotechnology (PBGB) Division, IRRI. Interviewed by Adrien Salazar. December 1, 2014.↩