Making the forest productive

Making the forest productive

Sarah Sax, MESc1

Abstract

Large-scale cultivation of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) spread throughout the tropics in the 20th century, with various socio-environmental effects, and is still ongoing. In the Peruvian Amazon, I examined the ways that the expansion of palm oil reaffirms or challenges existing power structures and identities that contribute to the uneven distribution of negative environmental impacts. I conducted over 30 semi-structured interviews with indigenous federations, government officials, NGOs, smallholders, and Shipibo-Konibo indigenous community members as well as conducting ethnographic research in three indigenous and one non-indigenous community. This article attempts to conceptualize the different legal, economic, and historical elements that contribute to one specific case of an oil palm plantation encroaching on the ancestral territory of the Shipibo village of Santa Clara de Uchunya. This case resulted in deforestation of 72–99% of the 6,874 ha of the land acquired, the majority of which falls within the ancestral territory of the Shipibo. Understanding the practices and power structures that contribute to cases of environmental injustice can ultimately help us design strategies for more sustainable and just resource management.

Los cultivos de palma aceitera (Elaeis guineensis) se han extendido en el trópico a lo largo del siglo XX, y su cultivo sigue en expansión, trayendo consigo efectos socioambientales. En la Amazonia Peruana, conduje una investigación para evaluar como la expansión de palma aceitera establece o reafirma las estructuras de poder y las identidades existentes que contribuyen a la distribución desigual de las cargas ambientales negativas. Para ello realice 30 entrevistas semi-estructuradas con federaciones indígenas, oficiales del gobierno peruano, ONG ambientalistas, productores de palma aceitera. También se realizaron investigaciones etnográficas en tres comunidades indígenas y en una comunidad no-indígena. Este articuló conceptualiza los diferentes aspectos legales, económicos e históricos que contribuyen a la expansión de una plantación de palma aceitera en el territorio ancestral de la comunidad Shipibo de Santa Clara de Uchunya. Este caso muestra una deforestación entre 72 y 99% de las 6,874ha de la tierra adquirida por la empresa. La mayoría de esta tierra se ubica sobre el territorio ancestral de los Shipibos. Así, entender las practicas y estructuras de poder que contribuyen en los casos de injusticia ambiental puede ayudar en la búsqueda de estrategias para un manejo de recursos más justos y más sostenible.

Introduction

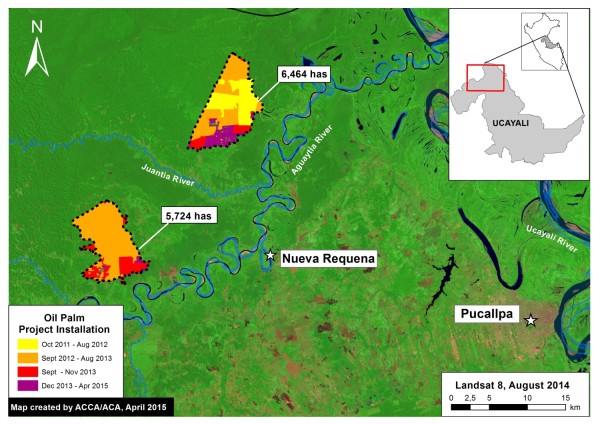

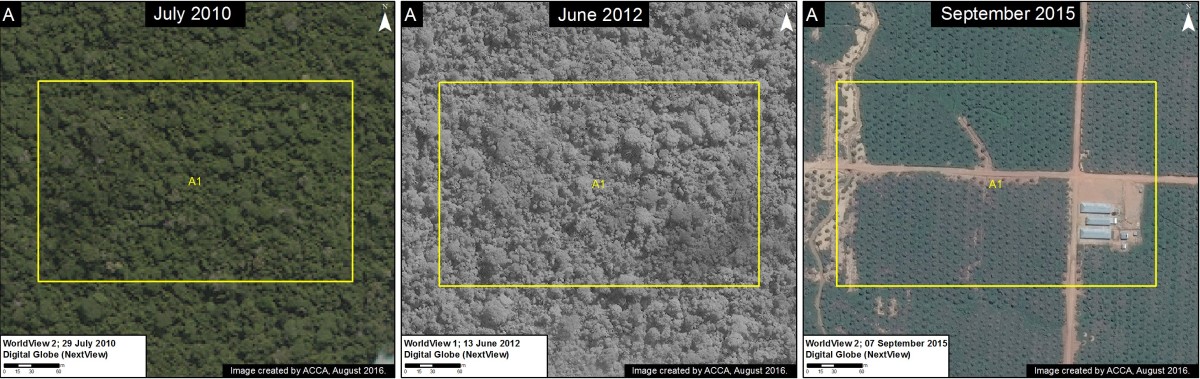

In April 2015, a conservation organization, Mapping the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP), posted the following image as their ‘map of the week’, under the title Image #4: Large-Scale Oil Palm Causes Deforestation of Primary Forest in the Peruvian Amazon (Fig. 1).

Two blocks of land are clearly demarcated, with different colour codes representing different timescales of deforestation. The rivers, lakes, plantations, and main cities are visible. Numbers show the rate of deforestation in these two areas over a 5-year period. This map, like so many remote sensing maps that depict deforestation, seems to the uncritical eye like an accurate, apolitical, even objective representation of reality. To the critical eye however, attention turns from what is made visible to what is rendered invisible in these maps (Harley 1992): historical inequities, lack of zoning, corruption, discriminatory policies and laws regulating forest use, property rights, and land grabbing. Life under the canopy of the forest is harder to depict via remote sensing than one might think.

The specific case captured by these images begins, according to LANDSAT time series data, in August 2010 when a company called Plantaciones de Pucallpa SAC started deforesting primary and secondary rainforest to create a palm oil plantation. Plantaciones de Pucallpa SAC operates as a subsidiary of United Oils Ltd, which belongs to the group United Cacao del Peru Norte. These companies are all owned or run by Dennis Melka, who owns over 25 such companies in Peru and is known locally as ‘the Melka Group’. The companies received their main funding from United Cacao Limited SEZC, which raised capital through the AIM (Alternative Investment Market, a sub-market of the London Stock Exchange) and later, the Bolsa de Valores de Lima.

Much of the rain forest in the images falls within the ancestral territory of the Shipibo-Konibo indigenous village of Santa Clara de Uchunya, near Nueva Requena. Between 2011 and 2013, Plantaciones de Pucallpa deforested approximately 6,000 ha of rain forest for the creation of an oil palm plantation, and another 5,000 ha for a second plantation nearby. In September 2013, they started planting oil palm, allegedly for sale to the European biodiesel market.

Subsequently, the Shipibo-Konibo village was stripped of many communally owned agricultural plots, was denied access to the forest for hunting, collecting and foraging, lost multiple sources of potable water because of contamination, and experienced heavy overfishing of their bay by the workers of the plantation. Santa Clara de Uchunya and several local NGOs protested and documented the ongoing deforestation by Plantaciones de Pucallpa SAC. As a result of the protests, the village of Santa Clara de Uchunya experienced continuous threats of violence by masked gunmen. The plantation cut off access to the village and members of the village were harassed in person and online by members of the press and adjacent villages. Indigenous leaders were forced to flee the city after receiving numerous death threats.

Various stakeholders, including the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), the National Government, the local environmental prosecutors office, and the village of Santa Clara de Uchunya brought cases against the plantation, starting as early as 2013. Despite these legal efforts, deforestation and expansion of the oil palm plantation continued until mid-2016, at which point the plantation was sold to a ‘foreign buyer’. The Ucayali plantations put up for auction were acquired by other companies also controlled by Melka: Plantaciones Agrícolas de Pucallpa SAC and Plantaciones Agrícolas de Ucayali SAC, later renamed Ocho Sur P SAC and Ocho Sur U SAC in late August 2016. By then, the damage and deforestation had been done. For the makers of maps such as Fig. 1, this date is where the conflict ends.

Generating the right resolution

How does one conceptualize something as complex as an environmental conflict that connects the most widely grown modern biofuel with 500 years of colonialization centered in a specific locality? What kind of analysis is needed to account for both the very real, local consequences and the larger political-economic circumstances that bring such conflicts into being?

Palm oil is a truly transnational commodity, and as such, any analysis of palm oil expansion would not be possible without attention to its global connections. From its humble beginnings, the oil palm tree (Elaeis guineensis Jacq., Arecaceae), originating in West Africa, was prized for the high oil content of its fleshy mesocarp, providing needed calories from the fat as well as being an important seasonal source of betacarotene for the local populations that grew it in diverse agroforestry systems. It was brought in the 19th century by the Dutch to Indonesia and used primarily as oil for steam-powered machines. Adapting to its new environment well, palm oil was eventually seized upon by the Indonesian government during its massive relocation program, the ‘estate-transmigration program’ or PIR-Trans, which operated from 1986–1994 (McCarthy 2010). It is now the most widely grown oil feed stock, grown for the most part in the humid tropics of Malaysia and Indonesia, financed by transnational companies, and sold around the world as cooking oil in South Asia, for cosmetics in North America, and increasingly as biofuel in Western Europe (Schouten et al 2011; Dauverge and Neville 2010; McCarthy 2010).

An analysis of oil palm is necessarily an analysis of globalization—an analysis of the social relations of an increasingly global production. An analysis of conflicts ensuing from the production of oil palm is not simply the encounter between two opposing stakeholders, although it is often conceptualized that way: The struggle of the Shipibo community of Santa Clara de Uchunya against the expansion of oil palm (FPP 2015). Nor is it just a conflict over a single natural resource, as in, Palm oil firms in Peru plan to clear 23,000 hectares of primary forest (The Guardian 2015). Such conceptualizations oversimplify and imply linearity, suggesting stable identities of people and places over time and a crossing of two distinct paths with a clear sense of directionality.

Instead, most environmental conflicts have tentacles that reach outwards, spanning across history, economies, knowledge systems, discourses, and space. The environmental conflict between Santa Clara de Uchunya and Plantaciones de Pucallpa this summer is such an example. Expressed largely as a land conflict between a foreign oil palm plantation, and a Peruvian indigenous community, deep in the central Amazon Basin, the roots of the conflict stretch outwards from multiple points that have converged in such a way as to produce a violent, inequitable outcome.

At the heart of environmental conflicts is the contestation of knowledge (Escobar 1996; Foucault 1980; Peet and Watts 1996). From the local to the global scale, a multitude of different people, researchers, organizations, government bodies, international environmental NGOs, companies, politicians, and arguably even commodities compete in creating discourses (Foucault 1982; see also Mintz 1985 and Agrawal 2004). These discourses influence how and why certain types of knowledge predominate and circulate; what ecological, legal, economic, and social outcomes they produce; and who is able to benefit and claim authority over resources. These resources include not only material ones such as land, but also immaterial resources such as truth, authority and power.

If this is the case, how does one research such conflicts with wildly varying geographic localities, identities, structures, and interrelationships? Political ecology offers a framework for analyzing environmental conflicts in a way that allows us to take seriously the local ecological impacts as well as the broader political-economic influences. Political ecologists ask how knowledge about, access to, and control over natural resources is mediated by social hierarchies and relations of difference based on power relations (Robbins 2004; Watts and Peet 2004). Therefore, political ecologists focus critical attention on the spatial entanglements of constructions and practices of knowledge (Tsing 2011). Environmental anthropology, precisely through its adherence to empirical and grounded ethnography, also helps us understand different notions, cultural visions, and situated forms of knowledge about the material world. Both political ecology and environmental anthropology help to show that there is no singular, unique, and universal concept of nature; there are in fact multiple ‘natures’ that are produced materially through economic, technical, and everyday practices, as well as symbolically and discursively through cultural interpretations, such as science (Goldman and Turner 2011; Görg 2011; Robbins 2013; Fairhead and Leach 2003). Any analysis therefore needs to capture both what is happening in the material, economic realm, as well as the social realm.

Resolution scale 1:10000

From 10,000 feet in the air, the oil palm plantation looks like a surreal cubist painting. Flying over a mosaic of lush shades of all different kinds of green of the forest, suddenly a square appears—neat rows of green dots, interspersed with lines of packed, dry red earth for 3 miles. Then the sea of green encases the square again. The land has been divided up into boxes; small boxes inside larger boxes, neat lines of homogeneity. It seems like a perverse footprint: the branding of capitalist rationality upon the rainforest.

Our ability to see and recognize human impact on land is framed by the names we have for things. When the conquistadores came to South America 500 years ago, they were not able to differentiate well between the selva—that wild expanse of virgin rainforest—and indigenous cultivated forest. For the Spanish, land that was not growing wheat or producing meat was not considered productive. The chacras and purmas2 of the original inhabitants, their swidden farms and communally managed lands were not seen, because the underlying logic that drove them was unrecognizable to the intruders. Instead, the conquistadores saw the land as unruly, wild land that needed to be domesticated (see Scott 1998) in order to be productive. This differentiation of ‘productive’ and ‘unproductive’, conferring the ability to create discrete types of lands and forests, has remained essentially unchanged for over 400 years and shapes understandings of this conflict.

As a perennial tree, the oil palm has an economic life span of around 25 years, which made it the perfect partner for the resettlement schemes, which resettled migrants on “unoccupied” land on Indonesia’s outer islands. Not only did this process increase the state’s authority over previously unruly territory, it also meant that resettled people were transformed by the state into law-abiding, tax-paying residents (Scott 1998). This logic was similarly adopted by the Peruvian government in 1992: illegal coca growers were transformed, via oil palm, from people functioning outside the formal market, to people now firmly within it. They became “productive” citizens, producing and amassing wealth, status, and control for the government from the forest.

However, the forestry law introduced in 2011 in Peru had sweeping effects, the most relevant of which is the prioritization of the forest as a resource. New forests, previously considered “unoccupied land”, were established. Now there are “communal forests”, “local forests” on top of already existing types of forests, such as the “forests of permanent production”. All in all, six new types of forests were created with defined ownership structures and use limitations. The transformation of the forest into a resource demands the need for defined ownership over that resource; a project for which, via capitalist logic, the state is best equipped (Dasgupta 1990; Vaccaro et al, 2013; De Jong and Ruiz, 2012).

Private property and capitalism, especially in their modern incarnation of neoliberalism, are difficult, or potentially impossible, to untangle from one another. Underlying the logic of neoliberalism is the need for the establishment of private property. For the state, private property is an effective way of socially constructing and politically controlling nature as well as people (Vaccaro et al, 2013). It is the division of land that ultimately creates territory. The use of territorialization strategies is a characteristic of almost all modern states (De Jong and Ruiz, 2012; Vandergeest and Peluso 1995). To have the power to exclude or include people within particular geographic boundaries, to be able to control what people do and their access to natural resources within those boundaries—that is where the power of the state lies (Vandergeest and Peluso 1995).

In 2010, encouraged by the Peruvian government’s embrace of neoliberal policies and erasure of many barriers to forest exploitation, the Melka Group moved into Peru and began the transformation of 12,000 ha of forest to highly efficient, highly productive oil palm plantations.

Resolution scale 1:100

To make land “productive” is not an easy job. The forest fights back with a vengeance, ensnaring the machete-wielding colonist farmer with vines and spikes, sending poisonous snakes and stinging ants. The Shipibo, traditionally fishermen who also practice swidden farming and whose ancestors have successfully cultivated the forest for thousands of years, find the type of permanent land-use change favored by the colonists highly unproductive. The topsoil, notoriously thin in the Amazon, loses nutrients quickly, assisted by the torrential downpour of the rainy season that leaches any remaining nutrients from the soil. According to the law, permanent land-use change is required for land to be considered “productive”. But productive for whom?

In Peru, if a smallholder is able to find ‘unoccupied’ land to manage ‘transparently, productively, and peacefully’ (La Ley de Reforma Agraria de Peru N° 17716) for 10 years, they receive the title to that property. Whether or not others already consider that land productive is irrelevant. Between 2010 and 2016, Plantaciones de Pucallpa acquired 233 such land titles from colonist farmers, who had been granted the land by the regional government. Some of that land was in what the Shipibo consider to be their ancestral territory, and many of the titles were later found to have been forged by the Regional Department of Agriculture.

Indigenous communal property management systems, driven by communal values of reciprocity, are often fundamentally at odds with the capitalist logic of productivity and individualism. Titling communal property is difficult in a system where private property is the norm and scant resources—financial, institutional, legal, and otherwise—exist for other types of land titling. Despite the presence of two large internationally-funded land titling projects, the last indigenous communal land title was granted over 15 years ago in Ucayali (AIDESEP 2015). If indigenous groups do receive title to communal lands, often the extension of land to which they gain title is far smaller than their traditional territory. Santa Clara de Uchunya, for example, received 218 ha of communal lands when they first applied for a communal land title in 1989. This is in stark contrast to the 50 ha given to each of the 17 non-indigenous individuals who were granted land titles in 2016, all falling within what the Shipibo consider their ancestral territory.

Although a signatory of the International Labor Organization Convention 169, which obliges the Peruvian government to recognize the “rights of ownership and possession of the peoples concerned over the lands, which they traditionally occupy”, Peruvian law institutionalized the definition in 2011, but still has no means by which to demarcate, measure, or title such lands.

The Sami have 108 different words for snow. The Tuareg have 7 different words for sand. Peruvian Law has six different names for forests, and none for ancestral territory; the Shipibo language has no word for private property. The conflict in Santa Clara de Uchunya begs the age-old question: if one has no name for something, can it actually exist?

Resolution scale 1:1

From below the canopy of the palms, the plantation is eerily silent. We reach the edge of the plantation after walking through the secondary forest adjoining the chacra of one of the residents of Santa Clara de Uchunya. Half a mile out, I can already see the edge effect produced by the plantation. Light intensity becomes greater, the humidity decreases, more shade-intolerant species appear, and walking becomes even more difficult as shrubs and vines inhabit the forest floor with greater density. As we reach the edge, I notice an increase in Cecropia, a notable pioneer species of recently disturbed forests, an ominous sign of destruction and loss. Stepping out onto the plantation after walking three miles through the secondary rain forest deafens me with silence and blinds me with the sudden intensity of the noontime Amazonian sun. The heavy use of pesticides and herbicides around the palm trees kills almost anything that would otherwise live here. Looking through the lines of towering palm trees, their trunks painted white to protect against the ferocious ants and rats. These opportunistic scavengers remind us of lessons we learnt as children to share, to give; they are nature’s last line of defense against man’s ceaseless need for control and exclusion.

What I see must be so much different from what the men wading through the dense underbrush see. For me, the forest is an overpowering, mysterious green force sustaining life, sustaining our atmosphere. Based on the commentaries the men exchange with me, this forest is their hunting ground, their pharmacy, their market, their playground, and a source of inspiration. The older Shipibo generation remembers more than the younger men. They remember how their grandparents used to live near here in a yaka (individual homesteads loosely connected to other homesteads). They remember how they would hunt ama, amen, and the bigger, more elusive (and more delicious) sachavaca3, the prized game of the forest. They remember the water that would run clear from the many sources, how this area used to provide the best caoba for the construction of their houses.

The older men also remember the stories that their grandmothers and great-grandmothers used to tell. Their great-grandmothers tell stories of how they were forced to flee the rubber barons who came for their parents. Rubber, it would seem, developed a taste for death and destruction in the Amazon before becoming a crucial commodity for the wars that would bring demise to thousands more. In the West we grieve the many soldiers lost in those wars that were enabled by the production of rubber, yet never do we mention the thousands of indigenous lives lost, the multitude of families ripped apart, the bodies mutilated, and the forests disfigured that form the basis for our own stories of loss and glory.

Their grandmothers tell stories of fighting with the papayeros4 who, so that Europe could satisfy its newfound taste for tropical fruit, would encroach upon the “free” land for a season, abandoning the papaya groves after they used up all of the soil nitrogen, leaving small piles of sickly fruit rotting in the sandy soil. Excess breeds excess, an alien concept for a culture for whom greed and hording is the biggest sin. Their parents too have stories to tell. The stories are often of illegal loggers, almost always closely followed by illegal coca growers. Two products, entwined both at their site of material production in the Amazon and at their site of social production in the West: a social production of desire. This desire is a desire for speed, a desire for fast money, fast furniture, fast lifestyles that necessarily requires the production of disposable land, disposable forests, disposable people.

Now these men, too, will have a story to tell their children. A story of oil palm, that by its insidious nature permeates every aspect of our lives here in the West: from the oil that fuels the cars we drive, the pastries we consume and the sugary spreads we smear on our bread, as well as the feed we give to chickens and cattle to satisfy our desire for flesh.

Above the crude barbed wire that blocks off what once was a hunting ground, a pharmacy, a market, a source of subsistence and livelihood for the Shipibo community of Santa Clara and is now an oil palm plantation, there hangs a sign that leaves a metallic taste of irony in my mouth: “Private Property—do not enter”.

References

Agarwal, A. 2004. Environmentality: Community, intimate government, and the making of environmental subjects. Current Anthropology 46, 161–190.

Dasgupta, P. 1990. The environment as a commodity. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 6, 51–67.

de Jong, W. & Ruiz, S.A. 2012. Strangers among trees: Territorialisation and forest policies in the northern Bolivian Amazon. Forest Policy and Economics 16, 65–70.

Escobar, A. 1996. Construction nature: Elements for a post-structuralist political ecology. Futures 28, 325–343.

Fairhead, J., & Leach, M. 1996. Misreading the African Landscape: Society and ecology in a forest-savanna mosaic. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Fairhead, J., & Leach, M. 2003. Science, Society and Power: Environmental knowledge and policy in West Africa and the Caribbean. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Finer M., Cruz C., Novoa, S. 2016. Confirming Deforestation for Oil Palm by the company Plantations of Pucallpa. Monitoring or the Andean Amazon Project: 41. URL: http://maaproject.org/2016/plantations-pucallpa/

Finer M, Novoa S 2015) Large-Scale Oil Palm Causes Deforestation of Primary Forest in the Peruvian Amazon (Part 1: Nueva Requena. MAAP: Image #4. URL: http://maaproject.org/2015/04/image-4-oil-palm-projects-cause-deforestat…

Foucault, M. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972–1977. Pantheon, New York, USA.

Foucault, M. 1982. The subject and power. Critical Inquiry 8, 777–795.

Goldman, M.J., Nadasdy, P., & Turner, M.D. (eds) 2011. Knowing Nature: Conversations at the intersection of political ecology and science studies. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA.

Görg, C. 2011. Shaping relationships with nature—adaptation to climate change as a challenge for society. Die Erde: Journal of the Geographical Society of Berlin 142, 411–428.

Harley, B.J. 1992. Deconstructing the map. In: Barnes, T.J. & Duncan, J.S. (eds). Writing Worlds: Discourse, text and metaphor. Routledge, New York, USA.

Hill, D. 2015, March 7. Palm oil firms in Peru plan to clear 23,000 hectares of primary forest. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/ andes-to-the-amazon/2015/mar/07/palm-oil-peru-23000-hectares-primary-forest

Holt-Giménez, E., & Shattuck, A. 2009. The agrofuels transition: Restructuring places and spaces in the global food system. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 29, 180–188.

Koh, L.P., & Wilcove, D.S. 2008. Is oil palm agriculture really destroying tropical biodiversity? Conservation Letters 1, 60–64.

McCarthy, J.F. 2010. Processes of inclusion and adverse incorporation: oil palm and agrarian change in Sumatra, Indonesia. The Journal of Peasant Studies 37, 821–850.

McCarthy, J., & Zen, Z. 2010. Regulating the oil palm boom: Assessing the effectiveness of environmental governance approaches to agro-industrial pollution in Indonesia. Law & Policy 32, 153–179.

Mintz, S.W. 1985. Sweetness and Power. The place of sugar in modern history. Viking, New York, USA.

Obidzinski, K., Andriani, R., Komarudin, H., & Andrianto, A. 2012. Environmental and social impacts of oil palm plantations and their implications for biofuel production in Indonesia. Ecology & Society 17, 25.

Robbins, P. 2004. Political Ecology. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, USA.

Robbins, P. 2013. Choosing metaphors for the anthropocene: Cultural and political ecologies. In: Johnson, N.C., Schein, R.H., & Winders, J. (eds). The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Cultural Geography. pp 305–319. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, UK.

Schouten, G., & Glasbergen, P. 2011. Creating legitimacy in global private governance: The case of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. Ecological Economics 70, 1891–1899.

Scott, J.C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press, New Haven, USA.

Forest Peoples Programme. 2017. The struggle of the Shipibo community of Santa Clara de Uchunya against the expansion of oil palm. Retrieved from http://www.forestpeoples.org/tags/palm-oil-rspo/struggle-shipibo-communi… %5Byear%5D=2015. Accessed April 2017.

Tsing, A. L. 2011. Friction: An ethnography of global connection. Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA.

Vaccaro, I., Beltran, O., & Paquet, P.A. 2013. Political ecology and conservation policies: Some theoretical genealogies. Journal of Political Ecology 20, 255–272.

Vandergeest, P., & Peluso, N.L. 2006. Empires of forestry: Professional forestry and state power in Southeast Asia, Part 1. Environment & History 12, 31–64.

Watts, M., & Peet, R. 1996. Towards a theory of liberation ecology. In: Peet, R. & Watts, M. Liberation Ecologies: Environment, development, social movements. 1st edition. 260–269. Routledge, London, UK.

Watts, M., & Peet, R. 2004. Liberating political ecology. In: Peet, R. & Watts, M. Liberation Ecologies: Environment, development, social movements. 2nd edition. 3–43. Routledge, London, UK.

-

Sarah Sax is a second year Master of Environmental Science student at Yale F&ES with an interest in tropical forest conservation and agriculture. Her research is focused broadly on understanding how knowledge about the environment is formed and the intersection of different types of knowledge systems in environmental policy, governance, and management.↩

-

Chacras denote agricultural land cleared and actively managed for a few seasons, especially to produce root staples such as yam and cassava. A purma is a chacra that has become overgrown and is used for other agricultural activities, mainly fruit harvesting and hunting.↩

-

Ama, amen are the Shipibo words for different types of animals commonly hunted that belong to the agouti family. Sachavaca is the Spanish word for Tapir.↩

-

Illegal colonist farmers who slash and burn parts of the forest for just a growing season to grow papaya.↩