The current population, distribution, and conservation status of the critically endangered White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis) in Bhutan

The current population, distribution, and conservation status of the critically endangered White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis) in Bhutan

Indra P. Acharja, MFS 20191

Abstract

In this research, I reviewed the historical distribution and change over time of the current population, distribution and conservation status of the critically endangered White-bellied Heron. Based on the data available on GBIF database, BirdLife International Data Zone, eBird observation datasets, published and unpublished project reports, museum specimens and 17 years of conservation efforts of Royal Society for the Protection of Nature (RSPN), it is apparent that the current WBH population is extremely small, and its geographic range has shrunken to less than 10% of its historically apprehended range. Although the current estimated global population is 50–249 (IUCN 2017a), fewer than 60 birds are confirmed persisting today in three range countries. The bird is rapidly verging extinction, and there is not any preserved gene pool outside natural habitats. Currently, active nests and the successful breeding pairs are only known in Bhutan although it is expected with the population in northeast India and Myanmar. The population in Bhutan has remained at 22–30 birds for the last decade despite constant conservation efforts and supplemented with juveniles fledging annually. The riparian habitats are transforming at an alarming pace because of the increasing number of hydropower projects and the fast-growing infrastructure development. It is severely affecting resource availability and isolating each micro population from others due to interruption of flyways and spatial barriers. In the long run, it will potentially affect the breeding and genetic viability for the deficient surviving population. Substantial conservation efforts are being made to protect and revive the population across the range countries today.

Introduction

White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis) is a large heron species of family Ardeidae, order Pelecaniformes, found in freshwater ecosystems of the Himalayas. It is categorized as critically endangered under the IUCN Red List of threatened species (IUCN 2018) and also the 94th species of the Top 100 EDGE Birds on EDGE of Existence list (EDGE of Existence, 2018). It was listed as threatened in 1988, uplisted to endangered in 1994, and to critically endangered since 2007 (IUCN 2017a, 2017b). Although the estimated population size is 50–249 adults (IUCN 2017a), fewer than 60 are confirmed to exist in the world today (Price and Goodman 2015).

Looking at the historical records and museum collections, it is evident that the bird was distributed across northern India, Nepal, Sikkim, northeast India, Bangladesh, and Myanmar during later 1800 to early 1900 (Baker 1928, BirdLife International 2001). Its potential presence in river systems of Bhutan was also predicted during the 1890s, but only confirmed in 1976 (Royal Society for Protection of Nature 2011). It was first observed by His Majesty the King Jigme Singye Wangchuck in Phochhu (Royal Society for Protection of Nature 2011). Historically known throughout the Himalayan region, it is now one of the rarest birds in the world having disappeared from most of its historical range including Nepal, Bangladesh and Northern India (BirdLife International 2001, IUCN 2017b). Currently, the White-bellied Heron is fragmented into three subpopulations in Bhutan, northeast India and Myanmar (Tordoff 2007, Maheswaran 2007, 2008, 2014, Mondal and Maheswaran 2014, Royal Society for Protection of Nature 2011). The most recent surveys in the range countries have found 29 individuals in Bhutan, 6-8 birds expected in India and fewer than 25 in Northern Myanmar (Price and Goodman 2015, RSPN 2018). Due to the widespread loss of riverine habitats, restricted distribution, and small breeding population, the global population is believed to be further declining (Pradhan 2007, Pradhan et al. 2007, IUCN 2017a).

Nests of White-bellied Heron (WBH) have been observed infrequently. The first nest, presumed to be of WBH was reported in Darjeeling, India around the 1890s and another in Myanmar in 1929 (Hume 1878, Ali et al. 1968, Royal Society for Protection of Nature 2011). There are no subsequent records of WBH nests for more than seven decades until an active nest was found in Bhutan in 2003 (Royal Society for Protection of Nature 2011). However, WBH nests are still scarcely sighted; no active nest has been identified in Myanmar, and there are no successful nest sightings in India, although two unsuccessful nests have been located recently (Maheswaran 2014). Therefore, the active breeding pairs and successful nests are known only from Bhutan at present.

The initiation of WBH conservation project in Bhutan dates back to early 2000. In 2002, Dr. George Archibald, co-founder of International Crane Foundation and his team, while birding along Mochhu, sighted a lone WBH in Rimchhu. With them was the late Ms. Ellie Schiller, a professional fisheries biologist, then Head of Felburn Foundation, who was thrilled by the view of feeding majestic heron, once thought to be extinct. She was inspired to provide financial support to begin protection and study the bird in Bhutan (Personal communication with Dr. Archibald 2015). Subsequently, the RSPN a national conservation NGO, led by senior ecologist Rebecca Pradhan initiated its first conservation project at the beginning of 2003 by circulating the pictures of the WBH and posting requests to report any sightings. Then in May 2003, the first nest was found in Domthang, Zawa a few kilometers upstream Digchhu from Kamechhu (RSPN 2006) which gave new hope to WBH conservationists.

In 2015, an international workshop was held in Bhutan where more than 40 heron conservationists from range countries and international experts came together to streamline the conservation program. The international WBH conservation strategy was finalized, and researches and conservation work are being carried out all across the range today (Price and Goodman 2015).

In the last 17 years, the RSPN has expanded the conservation works across the country. The distribution, feeding, and nesting habitats have been mapped, education and advocacy programs have been conducted across the country, several types of researches have been carried out, dozens of nesting sites have been identified, and population trend is closely monitored for nearly two decades. In 2011 RSPN also conducted an experimental artificial incubation and captive rearing by collecting eggs from a wild nest at Phochhu. It was a success; a chick was hatched and raised in captivity for 134 days before releasing into the wild. This experiment provided an opportunity to understand the developmental biology and also the confidence in the captive breeding program as a potential approach to recover and maintain an ecologically effective wild population.

Despite concerted efforts by the RSPN and researchers from home range countries, very little is known about the breeding, fledging, post-fledging behavior, dispersal, philopatry, reproductive age, lifespan, and other life history of the bird. In this paper, I summarized the historical distribution and change over time, population trend and nesting records in Bhutan for the last 16 years and the current conservation status of this critically endangered bird.

Methodology

Data on historical distribution and occurrence were collected from GBIF database (GBIF.org 2019) which includes records from eBird observation datasets, iNaturalist, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, naturgucker, Natural History Museum (London) Collection, Literature-based species occurrence data of birds of Northeast India, American Museum of Natural History, Yale Peabody Museum Collection and IUCN Species Red List database. Additional information was collected through a comprehensive literature review of historical field notes including Stray of Feathers; A Journal of Ornithology for India and its Dependencies 1878, which reflects the first discovery of White-bellied Heron.

Information on distribution, population, nesting and breeding history in Bhutan was collected from RSPN’s database, annual reports, and project reports. Additional background information on feeding and breeding ecology and community engagement in the conservation of the WBH were obtained from Rangzhin, a quarterly newsletter of RSPN since 1994. The microhabitats and the population trend in each microhabitat were collected from the WBH annual population survey reports which the RSPN has systematically carried out since 2003.

From 1 June to 27 July 2018, we also revisited 14 of the 22 old and new nesting sites and we verified the location of each nest with GPS, and collected additional information on vegetation and biogeography of the area. We could not collect data from four nests at Nangzhina because of monsoon and lack of accessibility. The nest tree at Basachhu was burned, and the nest tree has fallen off, and a landslide eroded the tree at Harachhu. We also located two new active nests with two and three juveniles in Punatsangchhu and Mangdechhu basins respectively which are included in the review.

Data analysis

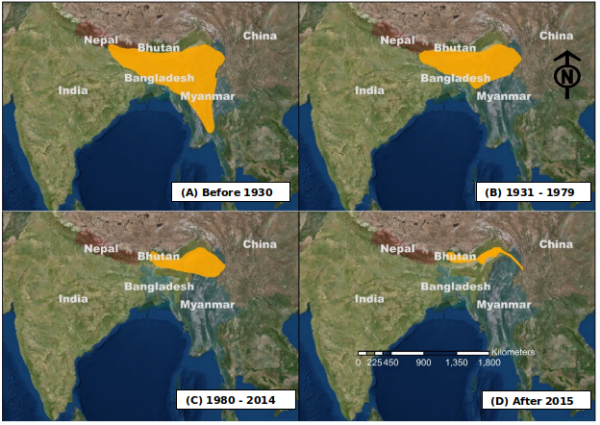

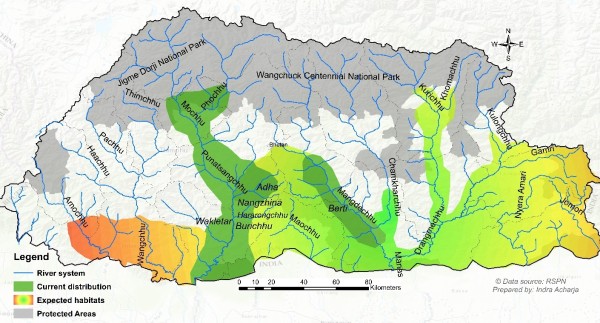

Data gathered from all sources were used to compile a database for the distribution and abundance of WBH across its range. The global occurrence observation database included GPS locations, count, date of observation and information source (fieldwork data, reports, published articles, museum collections, eBird datasets). Based on available occurrence observation data gathered, I produced global distribution maps for four periods, historical; before 1930, fairly recent; 1931–1979, recent; 1980–2014; and present; after 2015 (BirdLife International 2001). I produced graphs to visualize the population trend and variation with additional habitats discovered in the last 16 years in Bhutan. Data from Bhutan augmented prior information about the occupancy of microhabitat and micro-populations based on the annual population surveys. I analysed the trend and graphically represented the variations in each microhabitat to understand the population dynamics at each site. Using the nesting data which includes the location of nests, successful or unsuccessful, new nest or reused and year of occupation, I produced a separate nest map which characterizes the spatial distribution of nesting habitats in Bhutan. All spatial data were processed and visualized using ArcMap 10.4 (ESRI 2019), statistical and graphical representations were done using MS Excel and the statistical software R version 3.5.1 (R Core Team 2019).

Results

Global distribution

The WBH distribution has shrunk by more than 90% in the last one and a half century. Historical ornithological literature shows that the bird occupied a large area of Himalayan foothills from plains of Nepal, across northeast India including, Sikkim, Darjeeling, West Bengal, Assam, Arunachal, Nagaland, Bhutan to southern Myanmar bordering with Thailand during first quarter of 20th century (Baker 1928, Ali 1993, Hancock and Kushlan 2005). During the second and third quarter of 20th century, it expatriated from most of the historical range, restricting itself to Bhutan, northern Assam, Arunachal and northern Myanmar. The bird has been declared extinct from Nepal, and also there are no recent records from West Bengal, southern Myanmar, and Bangladesh suggesting that the overall range has contracted substantially (Fig.1).

Fig. 1. Change in the distribution (orange) of White-bellied Heron over the century and current global distribution.

Distribution in Bhutan

Although the possibility of WBH occurrence in Bhutan was foreseen during the 1890s (Baker 1928) there were no recorded sightings before 1976 (Royal Society for the Protection of Nature 2011). Starting 1990, the sighting of WBH along the Phochhu, Mochhu, and Punakha increased substantially (RSPN 2006). A local observer at Phochhu remembers seeing a few birds feeding in the area almost every day since 1992 and he has recently expressed that it is becoming rarer to see one every day (Personal communication with Mr. Kinley Penjor, 2018). Beginning 2003, the RSPN initiated the WBH conservation project which resulted in the discovery of the birds in several other locations along the Punatsangchhu basin and also in Mangdechhu since 2006. Today, it has been observed at more than 14 microhabitats which are believed to be used regularly. As a result of the nationwide inventory conducted by RSPN and with the observation by birdwatchers, the distribution range in Bhutan expanded from previously expected 600m–1200 m.a.s.l to Chir Pine dominated temperate forest in the inner Himalayas up to 1500m to Moist-broadleaved forest below 150m in the south. In recent years, it was also sighted a few times from Kurichhu and Drangmechhu in eastern Bhutan, if confirmed it will potentially double the range in the country (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The White-bellied Heron current distribution and expected habitat range in Bhutan.

Population in Bhutan

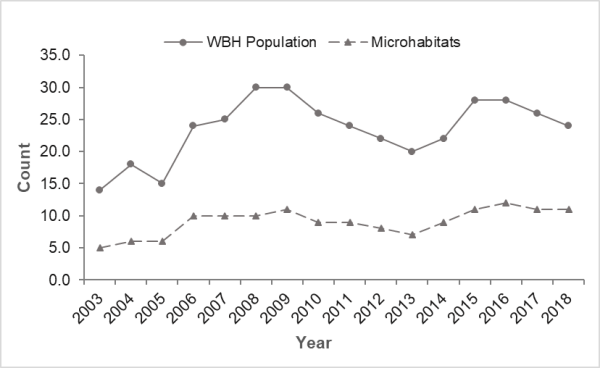

The RSPN conducted the first comprehensive WBH population census in 2003. During the census, 14 birds were counted from five locations along the Punatsangchhu. For the next six consecutive years, the population and number of new sites increased to all-time highest in 2009 with 30 birds counted from 11 locations (Fig. 3). However, the apparent increase in population size was directly influenced by the discovery of additional birds in new habitats while the total number of birds in each habitat had always remained the same or had decreased. Despite the discovery of birds from several new habitats in recent years and 2–6 additional juveniles fledging annually, the population in Bhutan has remained at 22–30 individuals for the last decade. Fig. 3 summarizes the population, number of occupied habitats and overall population trend in Bhutan for the past 16 years.

Fig. 3. The White-bellied Heron population count and the trend and the number of microhabitats the bird occupied each year for the past 16 years in Bhutan.

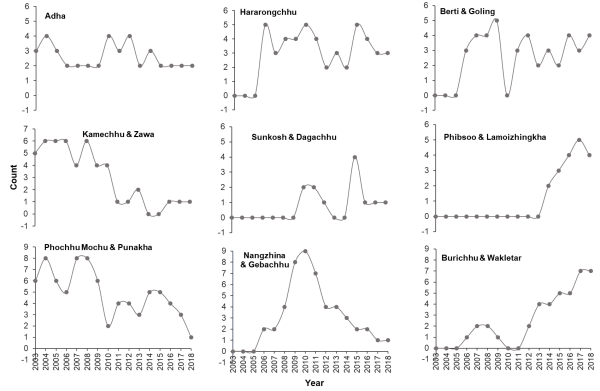

There is a noticeable change in population in important microhabitats. According to RSPN’s annual census, the population in all older habitats (Phochu, Mochhu, Punakha, Zawa, Kamechhu, Adha and Nangzhina) has drastically declined over the years (Fig. 4). The Phochhu and Mochhu area had eight birds during 2007 and 2008, but there is hardly one bird visiting the area presently.

Fig. 4. The White-bellied Heron population count and the trend in key microhabitats in Bhutan for the past 16 years.

Similarly, no birds were seen after 2013 in Zawa and the Kamechhu area; the oldest nesting site, where 6–8 birds were found before 2008. Overall the trend is also decreasing in Adha, Nangzhina and close by areas which were the most preferred feeding and nesting habitats until 2010. However, the population in Berti and, Goling sites was highest in 2009, no birds were seen during the 2010 census, but it is on increasing trend today.

In recent years more birds are being sighted in lower regions of Punatsangchhu and Mangdechhu basins, which are also newly discovered sites. The data indicate that the Burichhu and Wakletar are most promising sites with both population and nests in a sharp increase. The bird had been in these habitats since 2005, although it started nesting only after 2013. The census record indicates that the population is fluctuating with comparatively fewer number of birds further downstream Punatsagchhu; Sunkosh and Dagachhu area.

In 2014 two WBHs were sighted in Phibsoo Wildlife Sanctuary (PWS) which is located at southern Bhutan, bordering with the Indian state of Assam. The area is at the altitude of 100 m.a.s.l and the vegetation is mostly moist-evergreen broadleaved forest. In 2016, another lone bird was sighted in Lamoizhingkha range adjacent to PWS which is the southernmost region of Punatsangchhu. Although the vegetation composition and climatic conditions are different from previously known habitats, 3–5 birds had been recorded for the past five consecutive years and frequency of sighting had been increasing in the area, particularly during the winter. The recent observation records also indicate an increase in lower regions of Mangechhu basin. A few birds have been sighted feeding and nesting more than 20 km downstream from previously sighted areas which have vegetation and climate comparable to PWS.

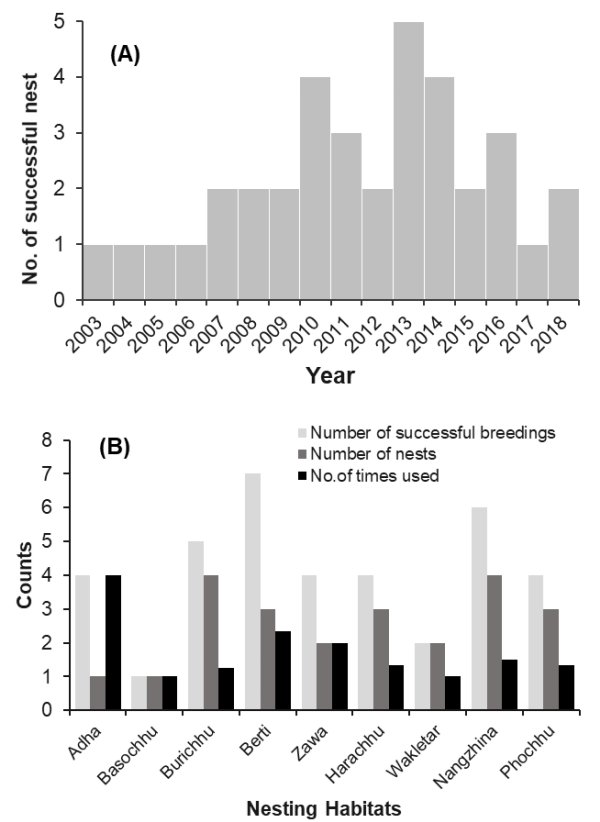

Fig. 5. (A) The number of successful White-bellied Heron nest and the trend for the last 16 years in Bhutan (B) Total number of successful breeding, number of nests and number of nests reuse in nine nesting habitats in Bhutan.

White-bellied Heron nests in Bhutan

Since the initial discovery of nests in 2003, RSPN has been able to locate 1 to up to 5 active nests for the last 16 years (Fig. 5A). The greatest number of active nests were discovered in 2013; one nest each in Phochhu, Adha, Burichhu, Hararongchhu, and Berti. Looking at the records, there are more variations in the number of successful breeding in recent years unlike prior to 2009, where one or two nests were repeatedly reused. The data also indicates that the number of nest reuse has decreased in recent years and more new nests are being built every year (Fig. 5B). Nests at Adha and Berti were reused four successive years while nests at Burichhu, Wakletar, and Hararongchhu had been used only once.

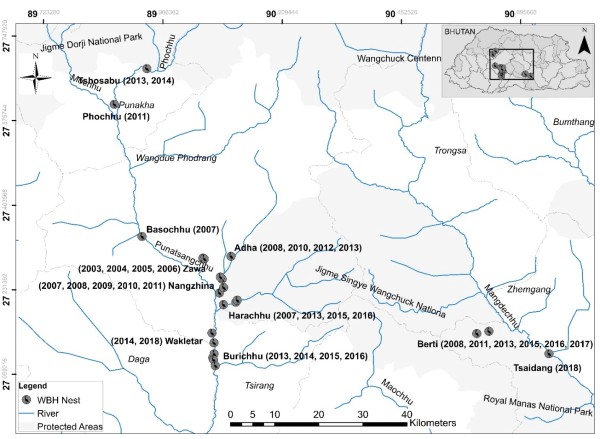

According to RSPN’s database, 22 WBH nests have been located in Bhutan starting in 2003 which are distributed in nine habitats (Fig. 5B & Fig. 6). Of the 22 nests, 19 are located in the Punatsangchhu basin and three in Mangdechhu Basin (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 The White-bellied Heron nests distribution and year of successful breeding in each nest from 2003–2018 in Bhutan. Each bird icon on the map represents a nest and the year in which the particular nest was used.

Discussion

The current population of White-bellied Heron is critically low, and its geographical range has shrunk to less than 10% of its historically occupied range. Although the current estimated global population is 50-249 (IUCN 2018), fewer than 60 birds are confirmed surviving today in three range countries as per the White-bellied Heron International Workshop held in Bhutan in 2015. This population size was determined based on the most recent survey conducted in each range country prior to the workshop. As WBH is relatively conspicuous and confined to a predictable habitat, it would appear that overall numbers might not be as great as estimated by IUCN, which is a cause for serious concern for the viability of population in the wild.

In Bhutan, WBH census is conducted every year between last week of February to the first week of March. It is a modified point count and line transect method which is best suited for the detection of rare and spatially confined herons. It is conducted for five consecutive days, and it had been systematically carried out for the past 17 years. According to current statistics, almost 50% of the surviving population and 100% of the successfully breeding population are in Bhutan. Although herons have been discovered in new sites in recent years, there is no net increase in total population. The data also indicate a constant decline in population from most of the former habitats which sustained a significant population for more than two decades.

It is difficult to know confidently why the birds are becoming scarcer, and this leads to speculation about the fate of these birds. Loss of feeding and nesting habitat due to land use change, disruption of flyways and increased disturbances are potentially the dominant factor driving the population decline. Most of the WBH habitats in Bhutan are under pressure today. The riparian habitats are transforming at an alarming pace with the increasing number of hydropower projects and the fast-growing infrastructure development. It is severely affecting resource availability and isolating one micro population from others due to interruption of flyways. In the long run, it will potentially affect the breeding and genetic viability for the small surviving population.

The local communities at Phochhu associate decline in the number of birds to the increasing frequency of rafting, picnicking and riverside recreational activities in the area. Similarly, a severe drop in the number of WBH sightings at Zawa was noticed after the beginning of the road and bridge construction at Digchhu, which is the only narrow entry into the valley. Similarly, a decrease in population in Adha and Harachhu were associated with new road construction and mega construction work at the Harachhu-Punatsangchhu confluence. This strongly suggests that human caused disturbances are driving birds out of the range.

However, significant conservation efforts are being made to protect and revive the population in the region. White-bellied Heron conservation strategy developed in 2015 collaboratively by experts and researchers from range countries has streamlined the conservation priorities. It is being implemented in Bhutan, India, and Myanmar. Surveys are also being conducted in neighboring countries like China and Bangladesh. In Bhutan, RSPN has mapped distribution across the country and identified essential feeding and nesting habitats. Consecutive population surveys have been conducted for nearly two decades, and population, nests, and juveniles are being closely monitored. RSPN has also educated, inspired and engaged local communities, students, researchers, institutions and policymakers in the conservation of the species. Currently, several types of researches to understand genetic diversity, ecology, biology, and threats are being undertaken throughout the habitat range. RSPN also has plans to tagged juveniles with satellite transmitters to study the movement, migration and resource utilization. Finally, RSPN has initiated a research and breeding facility center in Bhutan which will secure an ex-situ gene-pool and a seed population to supplement the wild population through captive breeding and release program in the near future.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted with financial support from Tropical Resources Institute (TRI), Yale F&ES summer funds, Carpenter-Sperry Internship, and Research Fund, South Asian Studies Rustgi Award and Royal Society for the Protection of Nature (RSPN). I am thankful to the executive director and RSPN management for allowing me to conduct this research. I extend my heartfelt gratitude to ecologist Rebecca Pradhan and my field crew Mr. Thinley Phuntsho, Mr. Pema Khandu, Mr. Tenzin Nima, Mr. Tshewang Lhendup and Mr. Sonam Tshering for their invaluable assistance in collecting data and sharing all the data. Finally, I am indebted to Professor Timothy G. Gregoire and Dr. Simon Queenborough for their unwavering guidance in materializing this article.

References

Ali, S. 1993. The Book of Indian Birds. Bombay Natural History Society.

Ali, S., and Ripley, S.D. 1968. Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan: Together with Those of Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan and Ceylon. Oxford University Press.

Baker, E. C. S. 1928. Sterna albifrons and other Oriental birds. Bull Brit Ornithol Club, 49, 37–40.

BirdLife International 2001. Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book. Cambridge, U.K.

EDGE of Existence 2018. Top 100 EDGE Birds: The Edge of Existence program. Retrieved September 9, 2018, from http:// www.edgeofexistence.org/species/white-bellied-heron/#overview.

ESRI 2019. ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10.4. Redlands, CA: Environmental Systems Research Institute.

GBIF.org. 2019. GBIF Occurrence. Downloaded on March 15, 2019 from https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.uwerzw.

Hume, A. O. and Davison, W. 1878. A revised list of the birds of Tenasserim. Stray Feathers 6, 1–524.

IUCN 2017a. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Verson 2017-2.

IUCN 2017b. Ardea insignis, in The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017.

IUCN 2018. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2018-1. Retrieved on September 05, 2018, from www.iucnredlist.org.

Kushlan, J. and Hancock, J. 2005. The Herons (Ardeidae). Bird Families of the World. Oxford University Press, New York.

Maheswaran, G. 2007. Records of White-bellied Heron Ardea insignis in Namdapha Tiger Reserve, Arunachal Pradesh, India. Birding ASIA 7, 48–49.

Maheswaran, G. 2008. Waterbirds of Namdapha Tiger Reserve, Arunachal Pradesh with special reference to White-bellied Heron Ardea insignis. Zoological Survey of India 108, 109–118.

Maheswaran, G. 2014. Update on the nesting White-bellied Heron Ardea insignis in Namdapha Tiger Reserve, Arunachal Pradesh, India. Birding ASIA 22, 8.

Mondal, H.S. and Maheswaran, G. 2014. First nesting record of White-bellied Heron Ardea insignis in Namdapha Tiger Reserve, Arunachal Pradesh, India. Birding ASIA 21, 13–17.

Pradhan, R. 2007. |emphWhite-bellied Heron Project, Annual Report 2005–2007. Royal Society for Protection of Nature: Thimphu. Unpublished report.

Pradhan, R., Norbu, T. and Frederick, P. 2007. Reproduction and ecology of the world rarest Ardeid: the White-bellied Heron. Royal Society for Protection of Nature. Unpublished report.

Price, M.R.S. & Goodman, G.L. 2015. White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis): Conservation Strategy. IUCN Species Survival Commission White-bellied Heron Working Group, part of the IUCN SSC Heron Specialist Group.

R Core Team 2018. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 3.5.1). Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved October 15, 2018, from https://www.R-project

Royal Society for Protection of Nature 2011. The Critically Endangered White-bellied Heron. Thimphu, Bhutan: 141.

RSPN 2006. Heron nest revisited. Rangzhin 28, 1–3.

RSPN 2018. Five new juveniles added to the existing population of the White-bellied Heron in 2018. Rangzhin 11, 1–3.

Tordoff, A. W., Appleton, T., Eames, J. C., Eberhardt, K., Hla, Htin, Thwin, Khin M. M, Zaw, S. M, Moses, S. and Aung, S. M. 2007. Avifaunal Surveys in the Lowlands of Kachin State, Myanmar, 2003–2005. Natural History Bulletin of the Siam Society 55, 235–306.

Citation

Indra. A.P. 2019. The current population, distribution, and conservation status of the critically endangered White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis) in Bhutan. Tropical Resources 38, 1–10.

-

Indra P. Acharja holds Master of Forest Science (2019) from School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, Yale University, USA, M. Sc. Forestry (2014) from Forest Research Institute (FRI) University, India and bachelor’s degree in Life Science (2012) from Sherubtse College, Royal University of Bhutan. Indra is also National Geographic Explorer and has received several grants and awards including National Geographic Explorer Grants, Andrew Sabin International Environmental Fellowship and TRI fellowship. Currently, Indra works for the Royal Society for the Protection of Nature (www.rspnbhutan.org) a head of the species conservation division. Indra's research focuses on studying the avian ecology, freshwater ecosystems, livelihoods, and their interlinkages in the Himalayan region. Currently, his work is largely focused on ecology, biology, and conservation of the critically endangered White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis) in Bhutan. In his spare time, Indra enjoys exploring the wilderness, wildlife photography, photogrammetry and he is a firm believer of the power of digital and visual storytelling.↩