More than meets the eye: The myriad drivers of land use conflict in Laikipia County, Kenya

More than meets the eye: The myriad drivers of land use conflict in Laikipia County, Kenya

Austin Scheetz, MESc 20201

Abstract

In 2017, violent conflicts over grazing rights ravaged Laikipia County, Kenya. I argue that the drivers of the conflicts are complicated, with four main causes—namely culture, economy, politics, and environment—interacting to catalyze unrest. By weaving together interviews of ranchers and pastoralists with literature on Laikipia’s history, I tell the story of Laikipia and illustrate how its present is a product of its past. Such an accounting of how Laikipia has developed should be considered by future policymakers when deciding how to reduce future conflicts.

Ikisiri Mwaka 2017, Kaunti ya Laikipia, Kenya, kulikuwa na migogoro mikali ya malisho. Sababu nyingi za migogoro zimependekezwa na waandishi mbalimbali, kwa mfano ukoloni na mienendo ya siasa. Ninafikiri kwamba kuna sababu nne kuu za migogoro. Sababu hizi ni utamaduni, uchumi, siasa, na mazingira. Nimetumia mahojiano ya wazungu na wafugaji wa Laikipia pamoja na utafiti mwingine wa historia ya Laikipia ili nieleze Laikipia imebadilikaje kutoka kabla ya ukoloni mpaka sasa. Sijaribu kuonyesha kila sababu za migogoro ya 2017, na sifikiri kwamba hizi sababu nne ni zote kwa migogoro. Ninatoa tu historia ya maendeleo ya Laikipia na ninaonyesha kwamba historia hii ni muhimu sana kwa kufahamu migogoro kwa wakati ujao.

Introduction

Dusty, barren pastures. Malnourished and emaciated livestock. An air of tension and desperation. Hundreds of thousands of cattle are flooding Laikipia from across county lines in neighboring Isiolo and Samburu Counties. These cattle are led by armed pastoral herders who demand grazing rights in their ancestral lands. It is an election year, and some say the armed pastoralists were incensed by the Member of Parliament (MP) for Laikipia’s northern district, Mathew Lempurkel. Landowners are fighting back, aided by Kenyan police, to maintain control of their borders. Dozens of people are being killed, tourism has halted, and wildlife such as elephants and lions are caught in the crossfire. These hardships and many others characterized a severe drought that Laikipia County, Kenya, faced in 2017.

In 2020, Laikipia is green after a healthy year of rain. Wildlife such as the endangered African wild dog are thriving, and the political situation is stable. However, the 2017 conflicts still live on in Laikipia’s collective memory. Though most of the incensed pastoralists in 2017 came from outside Laikipia, ranchers nonetheless seek to pacify the neighboring, resident pastoralists. Most ranchers across the county are selling permits to allow pastoralists legal grazing rights on private ranches. Many ranches have offered these permits since the early 2000’s, but the 2017 conflicts have people reeling. Many ranchers question whether the permitting system will prevent conflict, and conservationists are calling for an end to overgrazing, hoping to eliminate one of the root causes of conflict.

Laikipia County is a rugged, semi-arid county in the Great Rift Valley region of central Kenya (Fig. 1). Laikipia is a plateau adjacent to the foothills of Mount Kenya. Much of Laikipia is covered in savanna and scrubland, with charismatic wildlife such as zebras, elephants, lions, and hyenas roaming freely. Very little land in Laikipia is formally protected, but privately-owned wildlife conservancies bring in large numbers of wealthy tourists and protect wildlife habitat. These wildlife conservancies double as private ranches, with thousands of cattle dotting the landscape. In addition to these (generally white) ranchers, Laikipia has a large pastoralist population, mainly from Maasai, Samburu, Pokot, and Turkana tribes.

Fig. 1. Location of Laikipia County (red) in Kenya. Source: de Jong and Butynski 2014

I spent June-August of 2019 in Laikipia County studying the effects of grazing permits in promoting conservation. I interviewed ranchers and pastoralists living across Laikipia County, asking them about their motivations for buying/selling permits and how the permits affect the ways they manage their livestock herds. By weaving together these interviews with literature on the history of Laikipia, this article will highlight the interconnectedness of politics, economy, culture, and environment. I tell four connected stories, each describing one important driver of the 2017 conflicts. These stories are important to understanding the political and cultural landscape of Laikipia as it exists today, and may offer a useful framework for policymakers and planners to prevent future conflicts.

Culture

In the 1800’s, long before the arrival of the British in Kenya, present-day Laikipia County was shared by hunter-gatherer groups and pastoralists. The pastoral community of Laikipia was dominated by the Laikipiak, who were cattle-herding pastoralists very similar in lifestyle to the famous Maasai tribe, even sharing a language. Meanwhile, hunter-gatherer groups such as the Mumonyot, Yakuu, and Ndigirri led much different lives, with some groups being famous for beekeeping (Cronk 2002).

Pastoralism is defined as the nomadic movement of herders with their livestock. In East Africa, tribes like the Maasai raise cattle, seasonally roaming across the landscape in search of grass and water. The pastoral way of life is one of booms and busts. In a semi-arid climate like Laikipia’s, droughts are an expected hardship that demand preparation. For the pastoralists I spoke to, this preparation generally involves increasing livestock numbers as much as possible during wet periods. That way, when droughts devastate their livestock herds, they have enough surviving animals to feed their family until the drought passes. This lifestyle is as characteristic of pastoralism today as it was 150 years ago, when the Laikipiak wandered the county feeding their cattle.

In 1874, the Laikipiak lost a major battle against an alliance of other Maasai factions (Fox 2018; Sobania 1993). The loss dispersed the Laikipiak across Laikipia County, where they began inter-mingling with the various hunter-gatherer groups occupying much of the county. Marriages between Laikipiak and hunter-gatherers became increasingly common into the 20th century, and the marriages slowly began exerting influence on the culture of the hunter-gatherer groups.

Hunter-gatherers in Laikipia used to be referred to pejoratively as il-torrobo by Maa-speaking pastoralists such as the Maasai and Laikipiak. The label was used to refer to “poor people who must live like wild animals”, and pastoralists indeed viewed the il-torrobo – or “Dorobo” as it has been anglicized – as lower-class (Cronk 2002). Although inter-marriages became common after the Laikipiak’s 1874 defeat, they did not come without stipulations. Laikipiak men often demanded livestock dowries, as is typical in pastoral culture, and expected pastoral lifestyles of the women who joined their families. Thus, after decades of transition and intermarrying, many hunter-gatherer communities slowly evolved into pastoralist communities. By 1935, when the British colonial government set up reserves for hunter-gatherers, this transition was far along and Maa (the language of the Maasai and Laikipiak) was the dominant language in the area (Cronk 2002).

The former Dorobo slowly reduced their dependence on cattle throughout the 1900’s even as they started calling themselves Maasai. In traditional Maasai culture, cattle are highly valued, being used as dowry, measures of wealth and status, and for important cultural ceremonies. Today’s pastoral community in Laikipia prefers to keep goats, though cattle remain important for cultural reasons (Fig. 2). Goats reproduce quickly, an important feature in the boom/bust landscape of semi-arid Laikipia. After droughts wipe out livestock herds, goat herds bounce back quicker than cattle herds (Anonymous pastoralist 2019). Goats are also generalists, able to eat woody stems and other fodder that other animals cannot (Hart 2008). This makes them easier to raise on the degraded rangelands of Laikipia. Finally, goats are much easier to sell than cattle since they represent a smaller investment. Such marketability is becoming increasingly important to pastoralists as the market economy reaches into the most remote corners of Laikipia (Hauck and Rubenstein 2017).

Fig. 2. Goat kids playing in a Maasai homestead. Credit: Austin Scheetz.

Economy

As the world rapidly globalized after World War II, Laikipia transformed in major ways. Many cattle ranches across the county began rebranding as wildlife conservancies to capture a share of the surging interest in African wildlife tourism. Laikipia became a national hub for beef and milk production as the Kenyan economy grew. Wealthy foreigners began purchasing tracts of land across the county (Anonymous rancher 2019).

The pastoral community had a different reaction to the globalized economy. The pastoralists I interviewed strongly wish to maintain their way of life, but are also eager to enjoy the benefits of the 21st century economy. Livestock, and particularly cattle, remain vitally important culturally. They are still slaughtered at weddings and used as dowry. However, pastoralists have entered the cash economy in force. While pastoral youth continue the herding duties they always have, their parents are diversifying economically. Many pastoralists work wage jobs, sending money back home to pay for food and school uniforms. Wealthy pastoralists have leveraged the 21st century economy to enhance their status in the community, sending their kids to college while paying others to herd their livestock for them (Hauck and Rubenstein 2017).

Instead of livestock solely representing abstract expressions of wealth, as they used to, they now also represent genuine liquid assets. Pastoralists’ shift towards rearing goats reflects this. Pastoralists need cash much more than they used to, and goats are very easy to sell in local markets. Many younger pastoralists I talked to are only interested in keeping enough cattle to pay dowries. They prefer to keep goats, selling them often to earn money for smartphones, clothing, and other material goods. An increasing number of pastoralists are attending school and university, paid for in part by revenue earned from the sale of goats. Cattle could also be used to purchase these items, but their higher monetary and cultural value makes them more difficult for pastoralists to give up.

The importance of the goat for today’s pastoral community cannot be overstated, but it comes with large environmental consequences. As my interviewees explained, goats can be much harder on the landscape than cattle. Cattle require grass and are unable to digest woody material such as stems and twigs. However, goats can eat twigs, shrubs, branches, and other material in addition to grass (Hart 2008). This enables goats to survive on degraded landscapes, a very attractive quality from the pastoralist perspective. However, such adaptability means that after a large herd of cattle, sheep, and goats moves through an area, there may be virtually no green plant life left in their wake (Odadi, Fargione, and Rubenstein 2017).

Due to their destructive capability and relatively low economic value, goats are not raised in large numbers by the ranching community of Laikipia. To ranchers, grass eaten by goats is grass that cannot be eaten by more profitable cattle or camels. When accounting for the woody material and shrubbery that goats take away from resident wildlife such as dik-diks and impalas, goats become even less appealing to ranchers (Anonymous rancher 2019). The disconnect between the ways ranchers and pastoralists view goats has caused conflicts between the two groups.

These conflicts are exacerbated when droughts or other environmental stressors reduce the available forage for livestock. During droughts, pastoralists often negotiate temporary access to private ranches to graze their animals, termed “crisis grazing” by ranchers. Ranchers are often reluctant to accept pastoral livestock since they see it as a threat to their tourism revenue, and they almost never accept goats due to their destructive potential (Fox 2018; Anonymous rancher 2019; Anonymous pastoralist 2019). The economic interests of ranchers and pastoralists are thus locked in conflict, a conflict which is aggravated during periods of resource scarcity.

Environment

While in the mid-20th century droughts occurred once every 10 or so years, by the 90’s they had increased to once every two years. Today, droughts are extremely unpredictable (Opiyo et al. 2015). Alongside these droughts comes devastation to livestock herds, with 2009 droughts in Kenya and Tanzania causing the deaths of up to 90% of Maasai livestock (Huho, Ngaira, and Ogindo 2011). Climate change threatens to make these droughts even more severe in the future than they are today (IPCC 2014).

To protect themselves from the effects of drought, the ranchers I interviewed choose to leave around 15% of their grass untouched. This gives them a bank to draw from when the rains fail. The resulting low densities of livestock also allow ranchers to foster wildlife habitat. The ranchers’ method of livestock rearing aligns with a Western model, where sustainable population sizes are chosen to maintain a long-term equilibrium. While this conservative approach does work for the ranchers to insure against drought, pastoralists view the uneaten grass as a waste of valuable resources (Anonymous rancher 2019; Anonymous pastoralist 2019).

As mentioned earlier, pastoralism in semi-arid East Africa follows a non-equilibrial boom/bust cycle, whereby livestock herd sizes fluctuate wildly in response to rainfall. During wet periods, pastoralists build up their livestock herds as much as possible so that they can weather the devastation that the inevitable dry periods will bring (Ellis and Swift 1988). This behavior by pastoralists mirrors the response of wildlife populations to drought shocks and allows them to keep larger herds as a community. However, these large livestock herds have a greater impact on the landscape, reducing habitat for wildlife and putting pastoralists at odds with ranchers who view the large livestock herds as damaging and unsustainable (Anonymous rancher 2019).

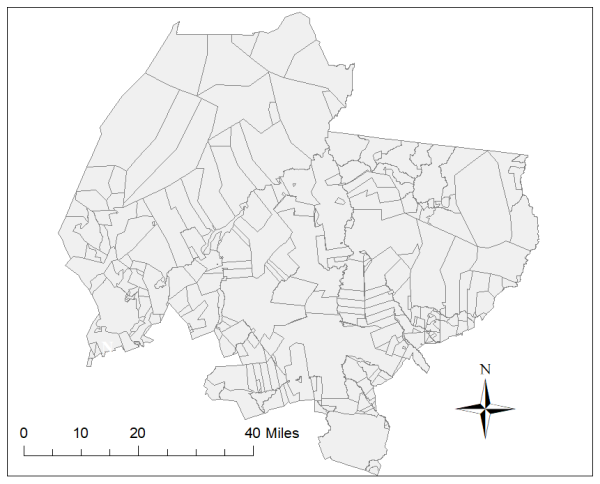

Traditionally, pastoralists respond to rainfall and grass shortages by moving somewhere that isn’t experiencing a shortage. For many of the pastoralists in Laikipia, this meant moving to the wet slopes of Mount Kenya when droughts pushed them out of their rangelands. However, the complicated network of private land holdings now present in Laikipia prevents pastoralists from being able to do this (Fig. 3). In order to reach Mount Kenya, most pastoralists must move through numerous private lands, negotiating passage with landowners along the way. This is not always possible, and complicates pastoralists’ ability to respond to droughts in the way they traditionally have. Conflicts between pastoralists and landowners arise from these incompatibilities (Anonymous rancher 2019; Anonymous pastoralist 2019).

Figure 3. Map of land parcels in Laikipia County.

Politics

British colonization of Kenya had profound impacts on the lifestyles of Laikipia residents. The Maasai used the term il-torrobo to refer to anyone without cattle, not intending for it to be an ethnic label. The British, misunderstanding this, applied the Dorobo to all hunter-gatherers in Laikipia and treated them as a homogenous group (Cronk 2002). The various Dorobo hunter gatherers often sold their land holdings to members of the neighboring Kikuyu tribe as part of longstanding trade relationships between the tribes. The British colonial government, seeking an excuse to usurp the Kikuyu land, pointed to those land sales as evidence that the Kikuyu and other tribes were exploiting the Dorobo. In the 1930’s, the British took much of the fertile Kikuyu land for themselves, managing the previously communal lands with a Western model of private land ownership. To accommodate the settlers, the British sent the Maasai south to a newly-created reservation, and gave the Dorobo their own reservation in the northeast corner of Laikipia County (Cronk 2002). Meanwhile, the Dorobo people had long since begun their slow evolution into pastoralism.

The British continued to give the Dorobo of Laikipia special status, providing them with reservations and protections even as the continued use of the term “Dorobo” ignored the large changes in their culture. To maintain the “purity” of the Dorobo, the British repeatedly deported Laikipia residents who did not conform to the British image of a “true Dorobo,” i.e. subsistence hunter-gatherers and beekeepers (Cronk 2002). Ironically, these deportations may have sped up the shift towards pastoralism. In order to avoid deportation and strengthen their claim to Laikipia land, members of pastoral communities married neighboring Dorobo, or il-torrobo as they still disparagingly called them (Cronk 2002). Today, most former Dorobo identify as Maasai or Samburu, and their ancestral languages have been largely replaced by the Maa language of the Maasai and Samburu people. Many still keep bees, a relic of their hunter-gatherer past, but cattle and goats have become the dominant income source for the pastoralists now living on the original Dorobo reserves (Cronk 2002).

As land in Laikipia passed back and forth between white and Kikuyu hands for the rest of the 20th century, Lakipia’s pastoralist population remained confined to the reserves originally created for the Dorobo. This led to overgrazing of the Dorobo reserves, as peoples who originally roamed the entire county were now confined to small reserves. After Kenyan independence in 1963, the Dorobo reserves evolved into the “group ranches” seen in Laikipia today, while the privately-owned settler land either remained with colonial descendants or was sold back to the Kikuyu. The Kenyan group ranch system was set up by the newly independent Kenyan government, and was intended to secure land tenure for pastoral groups in the post-colonial system of Western-style land ownership. The group ranch system allows pastoralists to form corporations to represent their interests, which then hold titles for land that is shared among the pastoralist community (Lewis 2015).

An ancillary goal of the group ranch system is to prevent overgrazing by giving pastoralists formal ownership of their land. In June of 1968, development agencies and Kenyan politicians hoped that giving land titles to pastoralists would push them to switch away from subsistence pastoralism. Federal agricultural ministers and the World Bank instead pushed for pastoralists to adopt commercial ranching operations. Such a shift to commercial ranching did not happen, and the pastoralist population continued to grow on the group ranches through to the present day (Lewis 2015). As the human population grew on a landscape that was already being overgrazed, per capita cattle holdings plummeted, a trend also observed elsewhere in Kenya (Desta and Coppock 2004).

In the leadup to the 2017 Kenyan elections, the pastoralists of Laikipia and its neighboring counties maintained lingering resentment. Pastoralists in central Kenya had experienced a dizzying sequence of displacements from their land, and anti-white sentiment was beginning to grow. The rise of local politician Mathew Lempurkel, a member of the pastoral Samburu ethnic group, contributed to this resentment. In 2013, Lempurkel promised pastoralists he would repatriate white-owned lands to Maasai, helping secure his election to Parliament (Fox 2018). As the 2017 election approached, Lempurkel again began stirring up anti-white sentiments among the pastoralist population of Laikipia and nearby Samburu and Isiolo Counties.

Ranchers, seeking to neutralize this growing resentment, began offering land-sharing programs to pastoralists by the year 2000. These land-sharing programs look largely the same today as they did then. Many ranchers sell grazing permits to pastoralists, which allow pastoralists to graze their cattle legally on private ranches as long as they pay the rancher a monthly fee for every head of cattle included. Ranchers generally set an aggregate number of cattle they are willing to take on, and give that number to the pastoralist community neighboring them. In some cases, the permits go to a few high-status community leaders, while in other cases the entire community allocates the total number of available permits amongst themselves, even buying and trading shares with each other (Anonymous rancher 2019; Anonymous pastoralist 2019).

However, many competing interests prevent ranchers from being able to provide as many permits as pastoralists need. Ranchers view high livestock populations as a threat to their eco-tourism operations. Since tourists visit ranches in their capacity as wildlife conservancies, ranchers fear that having too many pastoral cattle will ruin the experience for their guests (Anonymous rancher 2019; Fox 2018). This fear drives a general hesitation to accept large numbers of livestock from pastoralist communities, which may worsen tensions with pastoralists. Most ranchers also refuse to allow goats onto their ranches, further driving a wedge between the two communities.

In 2017, a severe drought struck Laikipia. According to my interviews, pastoralists ran out of grass on their group ranches and were forced to ask ranchers for help. Many ranchers agreed, offering crisis grazing to pastoralists to ease the drought burden. However, crisis grazing is generally only granted to ranchers’ immediate neighbors. Pastoralists from outside the county, who did not benefit from such arrangements, moved in to Laikipia at the urging of MP Lempurkel (Fox 2018). These armed “invasions,” as ranchers termed them, resulted in the deaths of at least 80 people (Gettleman 2017). Hundreds of thousands of cattle were illegally moved onto private ranches, and livestock thefts and wildlife killings became common.

Conclusions

The story of white colonists making money off of indigenous land is ubiquitous, and would seem to be sufficient explanation for the conflicts that struck Laikipia in 2017. However, Laikipia has also been the site of paradigm-shifting changes in economy, culture, and environment that cannot be ignored when analyzing the 2017 conflicts or even the period that has followed.

In fact economic, cultural, environmental and political pressures all played a role in instigating the 2017 conflicts. If the Dorobo had not merged with the Laikipiak and Samburu pastoralists, there may not be any pastoralists in Laikipia today. The reason the Dorobo groups were allowed to maintain any land in Laikipia is precisely because the British did not view them as pastoralists. After the Dorobo became decisively Maasai, the continued land-grabbing in Laikipia prevented them from carrying on the pastoral lifestyle as the Laikipiak once could. Pastoralists were blocked from their traditional grazing areas by a mosaic of private land holdings, even as environmental pressures mounted. Economic diversification has helped pastoralists mitigate this, offering them alternative income options in the face of limited mobility. However, their diversification strategies often include goats, which themselves need land to graze on.

The grazing permits that are nearly ubiquitous in Laikipia are one response to the conflicts arising from the interconnected histories I have described. However, the grazing permit system has two main limitations. Firstly, permits are not offered for goats. To fully accommodate pastoralists’ changing culture and increased market integration, permits would need to include goats as well as cattle. Secondly, grazing permits are only offered to pastoralists living immediately next to ranches. Such spatial limitations in the availability of permits may drive resentment among excluded pastoralists living in nearby Samburu or Isiolo Counties. These are the very same pastoralists who invaded Laikipia in large numbers in 2017.

The interconnected issues described herein are critical to understanding the complicated relationships between pastoralists and ranchers in Laikipia. The story of Laikipia’s pastoral community is one of displacement, environmental stress, and subsistence. Pastoralists’ relationship with each other, political elites, the economy, and the environment are all very important to understand if local stakeholders hope to prevent future conflicts. The story of Laikipia also provides a framework to analyze post-colonial conflicts in other systems. Across the world, there are fierce land conflicts that demand resolution, and a holistic understanding of how these conflicts came about is integral to the effort to resolve them.

References

Anonymous pastoralist. 2019. Pastoralist Interview by Austin Scheetz.

Anonymous rancher. 2019. Rancher Interview by Austin Scheetz.

Cronk, L. 2002. From true Dorobo to Mukogodo Maasai: Contested Ethnicity in Kenya. Ethnology 41, 27–49.

Desta, S. and Coppock, D.L. 2004. Pastoralism under pressure: Tracking system change in southern Ethiopia. Human Ecology 32, 465–86.

Ellis, J.E. and Swift, D.M. 1988. Stability of African pastoral ecosystems: Alternate paradigms and implications for development. Rangeland Ecology & Management / Journal of Range Management Archives 41, 450–59.

Fox, G.R. 2018. Maasai group ranches, minority land owners, and the political landscape of Laikipia County, Kenya. Journal of Eastern African Studies 12, 473–93.

Gettleman, J. 2017. Loss of fertile land fuels ‘looming crisis’ across Africa. The New York Times, July 29. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/29/world/africa/africa-climate-change-ke….

Hart, S. 2008. Meat Goat Nutrition. In Proc. 23rd Ann. Goat Field Day, 58–83. Langston, OK: Langston University. URL: http://www.luresext.edu/sites/default/files/2008%20Field%20Day.pdf.

Hauck, S. and Rubenstein, D.I. 2017. Pastoralist societies in flux: A conceptual framework analysis of herding and land use among the Mukugodo Maasai of Kenya. Pastoralism 7, 18.

Huho, J.M., Ngaira, J.K.W., and Ogindo, H.O. 2011. Living with drought: The case of the Maasai pastoralists of northern Kenya. Educational Research 2, 779–89.

IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Edited by R. K. Pachauri, Leo Mayer, and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva, Switzerland: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Lewis, A. 2015. Amboseli Landscapes: Maasai pastoralism, wildlife conservation, and natural resource management in Kenya, 1944–Present. Michigan State University.

Odadi, W.O., Fargione, J., and Rubenstein, D.I. 2017. Vegetation, wildlife, and livestock responses to planned grazing management in an African pastoral landscape. Land Degradation & Development 28, 2030–38.

Opiyo, F., Wasonga. O., Nyangito, M., Schilling, J., and Munang, R. 2015. Drought adaptation and coping strategies among the Turkana pastoralists of northern Kenya. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 6, 295–309.

Sobania, N. 1993. Defeat and Dispersal: The Laikipiak and Their Neighbours at the End of the Nineteenth Century. pp 105–119. In: Spear, T. & Waller, R. (Eds). Being Maasai: Ethnicity and Identity in East Africa. Boydell & Brewer.

Citation

Scheetz, A. 2020. More than meets the eye: The myriad drivers of land use conflict in Laikipia County, Kenya. Tropical Resources 39, 00–00.

-

Austin is … .↩︎